Not since the loss of the steamer Chusan in the great gale of October 1874, has so sad a disaster occurred at Ardrossan Harbour as that which took place on Monday morning last (1 March 1880). Sabbath was by no means stormy, but towards evening a gale which blew in fitful squalls of great violence sprung up and about midnight it had reached its climax. A few, but only a few in Ardrossan, whose sleep was broken by the storm, were aware that a ship's crew were in danger of their lives only a mile and a half off and that the lifeboat's men had gone to the rescue. But so it was and there would have been congratulation and thanksgiving had the rescue been affected without loss of life. But the gallant attempt to save life, by misadventure was only partially successful, two of those who had gone out in their noble mission of life saving returned not alive, and, with two of the crew, found death within sight of friends and home.

A boat went curtseying over the billows

Long I looked for the lads she bore

On the open desolate sea

And I think they sailed to the heavenly shore

For they came not back to me

Poor fellows! They met death in the path of duty

But this deed of theirs shall long be remembered in Ardrossan and live

Written on the various pages of the past in rosy characters of love

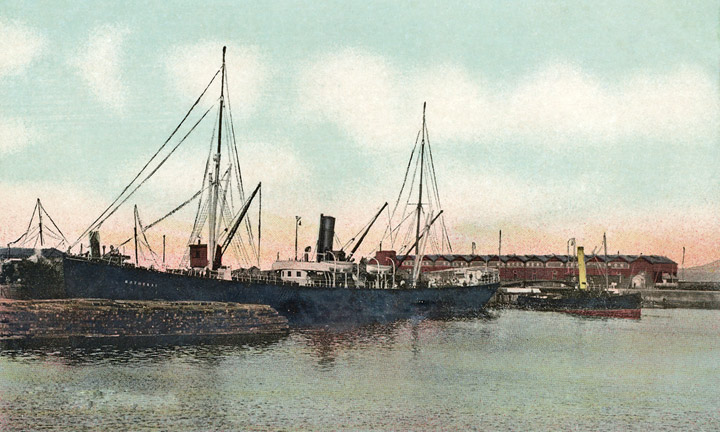

The

barque Matilda Hillyards of Yarmouth, Nova Scotia, 600 tons burthen, Mr John

Anderson, master, from Dieppe for Ardrossan, with a cargo of chalk on board

as ballast, intending to take in a cargo of iron for the States, made for Ardrossan

harbour (shown right in the early 1900s) between eleven and twelve o'clock on

Sabbath evening (29 February 1880). At this time the night was bleak and dirty,

the wind blowing in stiff gusts from west-south-west and Captain Steele, harbour

master, with the pilots and others, were on the lookout for vessels that might

require assistance. They observed the Matilda Hillyards when she was three or

four miles from shore, flash lights asking for assistance and the signal was

returned. Steps were at once taken to have the vessel safely stowed when she

came in. Although a considerable sea was running, no danger was expected from

the attempt to enter the port but the vessel was watched carefully and, as she

came on in the direction of the Horse Island, she was seen suddenly to haul

her head to the north or north west. This was done evidently for the purpose

of keeping the ship clear of the rocks, but the movement was unsuccessful and

in a short time afterwards, to the horror of the onlookers at the harbour, the

vessel drove on the island. Captain Steele, immediately on seeing what had occurred,

gave orders for the lifeboat, the Fair Maid of Perth, to be launched and despatched

a man to call out the crew. He also instructed that the harbour tug, the Terrier,

should be got in readiness to tow the lifeboat to the distressed ship. The crew

of the lifeboat responded promptly to the summons and the boat was launched

and manned by about half-past twelve o'clock, the crew consisting of thirteen

hands, under the command of Mr William Breckenridge, coxswain. The lifeboat

was, without loss of time, taken in tow by the Terrier and both proceeded to

the scene of the wreck. On getting to the windward of the island the lifeboat

was let go and the tug returned to the assistance of the brig Alexandria, which,

as we have said, was at anchor off the mouth of the harbour and in a somewhat

dangerous position. Meanwhile, the lifeboat pulled round the island to the wreck

which was lying on the east side of the rocks but it was found impossible to

board her on account of the height to which she had been driven on the rocks

and the roughness of the sea. The lifeboat thereupon returned to the lea of

the island and finding a favourable sound for landing, a portion of the crew

succeeded in getting ashore, it being hoped to reach the ship in this way. So

soon as the men had landed on the island, they scrambled across the rocks to

where the ship was lying and proceeded, with the assistance of lines which they

took with them from the boat, to establish communication with the crew of the

ill-fated ship. These movements, it will easily be understood, could not be

seen from the harbour and as the hours were fleeting rapidly without any intelligence

coming from the wreck and the storm was increasing in violence, some anxiety

was felt for the safety of the lifeboat and its gallant crew. The tug, which

was in charge of Mr Robert Bannatyne, accordingly left the harbour and sailed

round the island and at first nothing could be heard or seen of the lifeboat.

A whistle was blown on board the steamer and, in answer two lights were shown

from the island, the signals being so far satisfactory as indicating the safety

of the crew. Mr Bannatyne returned to the harbour and reported what had been

seen. The vessel, it was also ascertained, had been driven a considerable distance

up on the rocks by the force of the waves of the advancing tide, that the fore

and main masts had gone by the board and that the sea was making clear breeches

over the hull. On the return of the tug from the wreck, a consultation took

place between the harbour-master and the tug as to whether it would be advisable

to proceed once more to the island and to take with them a rowing boat, in order,

if possible, to render assistance to the crew of the life boat but as the storm

had become even worse that it was before, it was deemed advisable to postpone

such an effort till daylight had arrived. In the meantime, arrangements were

made for the expedition so soon as it could be undertaken with safety. The harbour

boat, a heavy craft of some eighteen feet keel, was made fast to the stern of

the tug and a crew of four men volunteered their services to man the boat, these

consisting of two of the hands of the steamer Brodick Castle (James McMillan

and James Leitch) and two harbour workmen (Patrick McKie and Edward Maloy).

The steamer left the harbour between six and seven o'clock and on reaching the

lea of the island comparatively smooth water was found. The four volunteers,

who sailed out in the tug, then leapt into the harbour boat and without much

difficulty they pulled into the sound where the lifeboat was lying in safety.

They found that the crew of the vessel, consisting of twelve men had been landed

on the island. This had been accomplished in a very praiseworthy manner. Communication

was first established with the vessel by means of a small line and afterwards

a large Manilla line was made fast. The men were dragged across this line to

the island but in the exposed situation in which the operations were conducted

the work was one of no small difficulty. When everything was in readiness for

leaving the island, the rescued men took their seats in the lifeboat, which

then contained twenty-five souls and the coxswain gave the order to proceed

to the tug which was lying-to in the lea of the island. The steamer was reached

in safety and the two boats were made fast, the lifeboat to the tug, having

a line of fifteen or twenty fathoms and the harbour boat, whose crew were taken

on board the tug, to the lifeboat. In this order, the crafts made for the harbour,

their movements being watched with intense interest from the shore. The news

of the wreck had spread rapidly among the inhabitants and, early as the hour

was, large crowds were assembled on the various quays. Mr Bannatyne for a considerable

distance steered his vessel so as to keep the lifeboat as much as possible head

on to the furious sea and when he had reached about half way across the bay

he changed his course in order to gain the harbour but endeavouring in the changed

direction to keep the lifeboat stern on to the waves. The danger of running

through a beam sea appears to have been quite recognised. All went well till

the boats were about 400 yards from the pier-head, when three tremendous seas

struck the lifeboat with the result that she capsized and flung her twenty-five

occupants into the boiling sea. Great excitement immediately seized upon the

onlookers and the excitement was mingled with amazement that the lifeboat, as

was expected she would, did not right herself. The majority of the immersed

men succeeded in clinging to the upturned boat. Two or three got onto the keel,

a number seized the gunwale and ropes which were attached to it and several

scrambled on board the harbour boat, which withstood the seas that upset the

lifeboat. Five others were less fortunate and four of these perished. The mate

and second mate of the Belfast steamer, North Eastern, lying in the harbour,

with the assistance of Captain Steele and others, immediately lowered the lifeboat

of that vessel and the two seamen first mentioned and two men who were at hand

leapt into it and proceeded to the assistance of the struggling men. This boat

succeeded in picking up two of the crew of the lifeboat who floated by means

of their lifebelts, but both were in a very exhausted state. No others with

the exception of those who were clinging to the life and harbour boats, were

seen and the boat returned to the harbour. The two men picked up were Alexander

Brodie and William Grier and when they landed every effort was put forth to

ensure their revival. Brodie soon recovered but in the case of William Grier,

who was very far gone, if life was not altogether extinct when he was brought

ashore, the means employed, first by the harbour-master and others and afterwards

by one of the doctors of the town, to produce animation failed. In the meantime,

the life and harbour boats had been slowly towed into the harbour, where the

crews were speedily rescued from their perilous positions. Most of the men were

in a very benumbed and exhausted condition but every one of the onlookers seemed

more anxious than another to render them assistance and all were comfortably

housed in a short time. The ship-wrecked crew were taken to the

The

barque Matilda Hillyards of Yarmouth, Nova Scotia, 600 tons burthen, Mr John

Anderson, master, from Dieppe for Ardrossan, with a cargo of chalk on board

as ballast, intending to take in a cargo of iron for the States, made for Ardrossan

harbour (shown right in the early 1900s) between eleven and twelve o'clock on

Sabbath evening (29 February 1880). At this time the night was bleak and dirty,

the wind blowing in stiff gusts from west-south-west and Captain Steele, harbour

master, with the pilots and others, were on the lookout for vessels that might

require assistance. They observed the Matilda Hillyards when she was three or

four miles from shore, flash lights asking for assistance and the signal was

returned. Steps were at once taken to have the vessel safely stowed when she

came in. Although a considerable sea was running, no danger was expected from

the attempt to enter the port but the vessel was watched carefully and, as she

came on in the direction of the Horse Island, she was seen suddenly to haul

her head to the north or north west. This was done evidently for the purpose

of keeping the ship clear of the rocks, but the movement was unsuccessful and

in a short time afterwards, to the horror of the onlookers at the harbour, the

vessel drove on the island. Captain Steele, immediately on seeing what had occurred,

gave orders for the lifeboat, the Fair Maid of Perth, to be launched and despatched

a man to call out the crew. He also instructed that the harbour tug, the Terrier,

should be got in readiness to tow the lifeboat to the distressed ship. The crew

of the lifeboat responded promptly to the summons and the boat was launched

and manned by about half-past twelve o'clock, the crew consisting of thirteen

hands, under the command of Mr William Breckenridge, coxswain. The lifeboat

was, without loss of time, taken in tow by the Terrier and both proceeded to

the scene of the wreck. On getting to the windward of the island the lifeboat

was let go and the tug returned to the assistance of the brig Alexandria, which,

as we have said, was at anchor off the mouth of the harbour and in a somewhat

dangerous position. Meanwhile, the lifeboat pulled round the island to the wreck

which was lying on the east side of the rocks but it was found impossible to

board her on account of the height to which she had been driven on the rocks

and the roughness of the sea. The lifeboat thereupon returned to the lea of

the island and finding a favourable sound for landing, a portion of the crew

succeeded in getting ashore, it being hoped to reach the ship in this way. So

soon as the men had landed on the island, they scrambled across the rocks to

where the ship was lying and proceeded, with the assistance of lines which they

took with them from the boat, to establish communication with the crew of the

ill-fated ship. These movements, it will easily be understood, could not be

seen from the harbour and as the hours were fleeting rapidly without any intelligence

coming from the wreck and the storm was increasing in violence, some anxiety

was felt for the safety of the lifeboat and its gallant crew. The tug, which

was in charge of Mr Robert Bannatyne, accordingly left the harbour and sailed

round the island and at first nothing could be heard or seen of the lifeboat.

A whistle was blown on board the steamer and, in answer two lights were shown

from the island, the signals being so far satisfactory as indicating the safety

of the crew. Mr Bannatyne returned to the harbour and reported what had been

seen. The vessel, it was also ascertained, had been driven a considerable distance

up on the rocks by the force of the waves of the advancing tide, that the fore

and main masts had gone by the board and that the sea was making clear breeches

over the hull. On the return of the tug from the wreck, a consultation took

place between the harbour-master and the tug as to whether it would be advisable

to proceed once more to the island and to take with them a rowing boat, in order,

if possible, to render assistance to the crew of the life boat but as the storm

had become even worse that it was before, it was deemed advisable to postpone

such an effort till daylight had arrived. In the meantime, arrangements were

made for the expedition so soon as it could be undertaken with safety. The harbour

boat, a heavy craft of some eighteen feet keel, was made fast to the stern of

the tug and a crew of four men volunteered their services to man the boat, these

consisting of two of the hands of the steamer Brodick Castle (James McMillan

and James Leitch) and two harbour workmen (Patrick McKie and Edward Maloy).

The steamer left the harbour between six and seven o'clock and on reaching the

lea of the island comparatively smooth water was found. The four volunteers,

who sailed out in the tug, then leapt into the harbour boat and without much

difficulty they pulled into the sound where the lifeboat was lying in safety.

They found that the crew of the vessel, consisting of twelve men had been landed

on the island. This had been accomplished in a very praiseworthy manner. Communication

was first established with the vessel by means of a small line and afterwards

a large Manilla line was made fast. The men were dragged across this line to

the island but in the exposed situation in which the operations were conducted

the work was one of no small difficulty. When everything was in readiness for

leaving the island, the rescued men took their seats in the lifeboat, which

then contained twenty-five souls and the coxswain gave the order to proceed

to the tug which was lying-to in the lea of the island. The steamer was reached

in safety and the two boats were made fast, the lifeboat to the tug, having

a line of fifteen or twenty fathoms and the harbour boat, whose crew were taken

on board the tug, to the lifeboat. In this order, the crafts made for the harbour,

their movements being watched with intense interest from the shore. The news

of the wreck had spread rapidly among the inhabitants and, early as the hour

was, large crowds were assembled on the various quays. Mr Bannatyne for a considerable

distance steered his vessel so as to keep the lifeboat as much as possible head

on to the furious sea and when he had reached about half way across the bay

he changed his course in order to gain the harbour but endeavouring in the changed

direction to keep the lifeboat stern on to the waves. The danger of running

through a beam sea appears to have been quite recognised. All went well till

the boats were about 400 yards from the pier-head, when three tremendous seas

struck the lifeboat with the result that she capsized and flung her twenty-five

occupants into the boiling sea. Great excitement immediately seized upon the

onlookers and the excitement was mingled with amazement that the lifeboat, as

was expected she would, did not right herself. The majority of the immersed

men succeeded in clinging to the upturned boat. Two or three got onto the keel,

a number seized the gunwale and ropes which were attached to it and several

scrambled on board the harbour boat, which withstood the seas that upset the

lifeboat. Five others were less fortunate and four of these perished. The mate

and second mate of the Belfast steamer, North Eastern, lying in the harbour,

with the assistance of Captain Steele and others, immediately lowered the lifeboat

of that vessel and the two seamen first mentioned and two men who were at hand

leapt into it and proceeded to the assistance of the struggling men. This boat

succeeded in picking up two of the crew of the lifeboat who floated by means

of their lifebelts, but both were in a very exhausted state. No others with

the exception of those who were clinging to the life and harbour boats, were

seen and the boat returned to the harbour. The two men picked up were Alexander

Brodie and William Grier and when they landed every effort was put forth to

ensure their revival. Brodie soon recovered but in the case of William Grier,

who was very far gone, if life was not altogether extinct when he was brought

ashore, the means employed, first by the harbour-master and others and afterwards

by one of the doctors of the town, to produce animation failed. In the meantime,

the life and harbour boats had been slowly towed into the harbour, where the

crews were speedily rescued from their perilous positions. Most of the men were

in a very benumbed and exhausted condition but every one of the onlookers seemed

more anxious than another to render them assistance and all were comfortably

housed in a short time. The ship-wrecked crew were taken to the  Eglinton

Arms Hotel (shown right in the 1960s) and several of the more exhausted of the

lifeboat men were attended to in the nearest places to which they could be conveyed.

Mr William Breckenridge, coxswain of the lifeboat, states: The lifeboat was

towed out near to the barque by the tug. After the tug dropped us, we ran down

past the barque and observing that she was high up on the rocks and that it

would be dangerous to go alongside, we ran the lifeboat into the sound of the

island, making her fast with a bower anchor. Six hands went on the island and

an attempt was made to get communication with the vessel. We spoke to those

onboard, instructing them how to act. We told them to stay on board till ebb

water, as the ship was keeping together. The mainmast of the vessel was standing

when we passed her but it was gone two minutes after. The foremast was cut away.

When on the island we burned six blue lights, but two did not go off. It was

a nasty place. Communication was obtained with the vessel by means of a small

line at first. Afterwards a large Manilla line was passed out to the vessel

and fastened to the rocks on the island. The men were all dragged across the

rope and landed on the island. When the tug came out we had just got the men

all ashore and were getting ready to go into the lifeboat. The tug, which was

lying to leeward of the island, came and took us in tow. There was a proposal

made that we should get into the tug. I think that would have been a prudent

course to have adopted. After getting fast to the tug, the lifeboat behaved

well till inside the Crinan Rock. There was a heavy sea and the lifeboat was

nearly under the tug's quarter. When the tugboat went ahead the rope tightened

and the lifeboat capsized before we had time to think of anything. The water

came over the starboard side and the lifeboat turned right over. All the men

were thrown into the water. A number of the men hung on to both sides of the

lifeboat. She never righted. All the hatches were closed and she should have

righted as everything had been done to ensure that. William Grier and Alexander

McEwan, the two men who were lost from the lifeboat, did their duty nobly both

on the island and in the lifeboat, while all the other members of the crew did

their best to save life. We were on the island from one o'clock till about 7

am, keeping up constant communication with the barque. Robert Bannatyne, master

of the harbour tug Terrier, states: Between twelve and one o'clock we took the

lifeboat in tow out to the barque, letting her go a little ahead of the ship

to drive down upon her with her anchor. We then left and came back to the harbour,

taking in the brig Alexandria. We then proceeded to the Horse Island, went close

to the barque and hailed her. We heard some persons calling and disonting, but

could not make out what they said. We thought they said "all right"

and we then returned to the harbour again. About four o'clock, we proceeded

round the Horse Island and getting to its lee side, with the view of getting

communication with the lifeboat, which we thought had got lost, because we had

not heard nor seen anything of her. We sounded the whistle and they showed us

two blue lights. We got no communication and heard nothing, only we knew they

were all on the island, from which the two blue lights were shown. We came back

to the harbour and reported what we had seen. It was not known whether the barque's

crew were on the island along with the lifeboat crew or not. Mr Craig and the

Harbourmaster Captain Steele, who were anxious and doing all in their power

to see that everything was right, suggested that a boat should be towed out

in order to get some communication with the lifeboat. About 6 am we took the

pilot in tow and four men along with us to man her. We towed her into smooth

water in the lee of the island where the four men went ashore. At this time

we could see the men coming from the barque towards the lifeboat. When the lifeboat

left the island we went towards her, taking her and the pilot boat in tow. The

four men did not remain in the pilot boat, but came on board the tug again.

I was getting the ropes ready to tow the boats and there was no one said they

would go in the tug. I understood no one wanted to go in the tug. I requested

the mate of the Arran boat and one of the men to take charge of the helm while

I went forward to see that the tug was kept clear of the rocks. Being forward,

I did not see the lifeboat capsise. After the lifeboat capsised, I came aft

and said we should go on slow, because we were so close to shore there was no

need to stop. The boat did not come right and we towed her into the harbour

bottom up, the men clinging to her. The sea was extraordinary heavy in the early

part of the morning. Another eye witness says: At a quarter past seven in the

morning, during the prevalence of a gale from the south-west, I noticed the

boats that went out to the wreck to leeward of the island. They were then making

for the harbour. Everything went well till they were midway between the island

and the pier. Then, as the steamer was about to go to windward of the half-tide

rocks, she drew up to the south-west in order the better to be clear of the

broken water. The lifeboat was then in tow astern and would not answer her helm

very cleverly and so she put her shoulder into the sea - the pilot boat being

still astern - or filled. There was a heavy sea running and much broken water

at the time. This caused her to capsise and the whole of the crew of the lifeboat

and the saved mariners who were in her, were thrown into the water. The men

hung onto her, evidently thinking she would right herself instantly, which should

have been the case with a boat of her class. Under the most adverse circumstances,

everyone scrambled for bare life. Most of the men succeeded in getting hold

of the life lines on her side which run round the boat and succeeded in climbing

onto the keel. In this way, they were towed into the harbour, sometimes more

under than above water. Some of the men holding on to the life lines were coming

in tow of the tug, head down. Two of the men - Brodie and Grier - were found

floating, in their life jackets, by a boat put out from the North Eastern, who

manned that vessels lifeboat and went out and picked up these two men. Brodie

came round but Grier expired shortly after he was taken into the boat. Two of

the sailors, the steward and another man, were lost in the casualty. McEwan

was got floating out from the pier about an hour afterwards. An eye witness

of what transpired overnight, till the close of the catastrophe, says:-About

a quarter past one, on Monday morning, I was awakened by the storm. At that

time it was blowing pretty stiff and I was curious enough to take a look out

of my window which faces the north shore. In and about the harbour, there was

a mixture of red, green and white lights which proved to be those of the brig

Alexandria and the tug. I also observed a white light towards the south end

of the Horse Island. This however, did not excite my attention at the time as

I thought it was that of a steamer going up the Clyde. After watching it for

a short time and not seeing it move, it occurred to me that it might be that

of a vessel on the island. Lifting an opera-glass, I looked towards the light

and could make out the loom of what I took to be a large vessel. I did not then

think of going out and returned to bed. I did not sleep, however, but watched

the light and about two o'clock observed two flash lights and then saw the tug

go out. I could not rest, so got up, dressed and went out. As I past the slip

at the fish market, I observed the carriage of the lifeboat in the water and

knew that she had gone out. When I got down to the Arran boat's berth, the tug

had just come in. The crew, on being questioned, said they had heard voices

on the island and supposed they cried out, "All right". They had a

doubt to this however. The master of the tug, who had got his face badly cut

by the towing hauser of the lifeboat, went home to have it dressed. It was deemed

necessary that the tug should go out again as soon as he had had this operation

performed as no sign from the lifeboat had been obtained for a considerable

time and it was feared she might have come to grief among the rocks. In the

interval, one of the coastguardsmen was dispatched to send up a rocket and a

blue light was burned at the Pilot-house. Neither of these signals was answered.

The master of the tug having returned, her lines were let go and she steamed

out. This would be about four o'clock. As she passed the old pier, a very heavy

squall came away. I think it blew then and for half an hour afterwards, harder

than at any other part of the night. The tug proceeded round the island by the

south end and 'came to' off the north end. In reply to her steam whistle, a

lantern was shown from the north end and two blue lights were burned from the

'spire.' The tug then returned on the same course as she had gone out. She came

into berth and the crew reported. They had heard nothing. They were of opinion,

though, that the ship's crew had not yet got ashore. This conjecture afterwards

proved correct. It was then suggested and agreed to that the tug should tow

out the pilot, or some other boat and that men should go on board the tug to

row the boat ashore, when they reached quiet water. The tug had to be coaled

first, both as the coals were needed and also for ballast, as the master was

afraid she mightcapsize, she being so light. The coaling took up a considerable

time and it was about half past six ere she was in trim for starting again.

She left the harbour about a quarter to seven with the pilot boat in tow and

proceeded inside the Crinan Rock to the north end of the island. Having got

into comparatively smooth water, four men got into the pilot boat and rowed

ashore. A considerable crowd had by this time collected on the old pier and

the proceedings were watched with intense interest. The crew of the ship had

just been landed on the island and they along with the lifeboat crew, proceeded

towards that part of the beach where the pilot boat had gone in and where the

lifeboat also lay at anchor. About a quarter past seven, the pilot boat pulled

off to the tug and her hands were taken on board. She was closely followed by

the lifeboat and the tug having passed a hawser on board she was taken in tow,

the pilot boat being astern of her. The tug went towards the south for three

or four hundred yards and then put about and stood in towards the Long Craigs,

for about the same distance, when she was headed for the harbour. Meantime the

lifeboat and pilot boat had been following her all right and remarks were made

on the quay how well the former was behaving. When the tug, however was for

the harbour, she would not follow, her rudder being seemingly useless, as she

was going along on the crest of a large wave, I was afraid at one time that

she was to be dashed against the tug. Having sunk in the hollow of a wave, her

rudder seemed to take effect and she was coming round. Just as she was doing

so, another wave caught her and carried her to leeward and her hawser tightening

and the next wave, a broken one, catching her on the quarter just at that moment,

in an instant, she was overturned and all on board were thrown into the water.

The tug had stopped and this gave the men an opportunity of laying hold of the

lifeboat, which remained bottom up. Three poor fellows had, however dropped

astern and those on board the tug, seeing they could do nothing to assist them,

did in my opinion, the best thing they could have done, namely steamed ahead.

So sudden had been the catastrophe, that those on the pier for a moment did

not seem to realise it. When they did, the excitement was beyond bounds. The

wives of the lifeboat men who had come on the pier wrung their hands in grief

and the crowd showed their sympathy by using all the means available, which

alas, were few, to rescue the drowning men. A lifeboat was promptly launched

from the North Eastern and five brave men - Mr Charles Adair, pilot along with

Messrs Bell, Todd, Arthur Spencer, Henry Cope and George Fergusson, the second

mate - pulled out to lend what aid they could.

Eglinton

Arms Hotel (shown right in the 1960s) and several of the more exhausted of the

lifeboat men were attended to in the nearest places to which they could be conveyed.

Mr William Breckenridge, coxswain of the lifeboat, states: The lifeboat was

towed out near to the barque by the tug. After the tug dropped us, we ran down

past the barque and observing that she was high up on the rocks and that it

would be dangerous to go alongside, we ran the lifeboat into the sound of the

island, making her fast with a bower anchor. Six hands went on the island and

an attempt was made to get communication with the vessel. We spoke to those

onboard, instructing them how to act. We told them to stay on board till ebb

water, as the ship was keeping together. The mainmast of the vessel was standing

when we passed her but it was gone two minutes after. The foremast was cut away.

When on the island we burned six blue lights, but two did not go off. It was

a nasty place. Communication was obtained with the vessel by means of a small

line at first. Afterwards a large Manilla line was passed out to the vessel

and fastened to the rocks on the island. The men were all dragged across the

rope and landed on the island. When the tug came out we had just got the men

all ashore and were getting ready to go into the lifeboat. The tug, which was

lying to leeward of the island, came and took us in tow. There was a proposal

made that we should get into the tug. I think that would have been a prudent

course to have adopted. After getting fast to the tug, the lifeboat behaved

well till inside the Crinan Rock. There was a heavy sea and the lifeboat was

nearly under the tug's quarter. When the tugboat went ahead the rope tightened

and the lifeboat capsized before we had time to think of anything. The water

came over the starboard side and the lifeboat turned right over. All the men

were thrown into the water. A number of the men hung on to both sides of the

lifeboat. She never righted. All the hatches were closed and she should have

righted as everything had been done to ensure that. William Grier and Alexander

McEwan, the two men who were lost from the lifeboat, did their duty nobly both

on the island and in the lifeboat, while all the other members of the crew did

their best to save life. We were on the island from one o'clock till about 7

am, keeping up constant communication with the barque. Robert Bannatyne, master

of the harbour tug Terrier, states: Between twelve and one o'clock we took the

lifeboat in tow out to the barque, letting her go a little ahead of the ship

to drive down upon her with her anchor. We then left and came back to the harbour,

taking in the brig Alexandria. We then proceeded to the Horse Island, went close

to the barque and hailed her. We heard some persons calling and disonting, but

could not make out what they said. We thought they said "all right"

and we then returned to the harbour again. About four o'clock, we proceeded

round the Horse Island and getting to its lee side, with the view of getting

communication with the lifeboat, which we thought had got lost, because we had

not heard nor seen anything of her. We sounded the whistle and they showed us

two blue lights. We got no communication and heard nothing, only we knew they

were all on the island, from which the two blue lights were shown. We came back

to the harbour and reported what we had seen. It was not known whether the barque's

crew were on the island along with the lifeboat crew or not. Mr Craig and the

Harbourmaster Captain Steele, who were anxious and doing all in their power

to see that everything was right, suggested that a boat should be towed out

in order to get some communication with the lifeboat. About 6 am we took the

pilot in tow and four men along with us to man her. We towed her into smooth

water in the lee of the island where the four men went ashore. At this time

we could see the men coming from the barque towards the lifeboat. When the lifeboat

left the island we went towards her, taking her and the pilot boat in tow. The

four men did not remain in the pilot boat, but came on board the tug again.

I was getting the ropes ready to tow the boats and there was no one said they

would go in the tug. I understood no one wanted to go in the tug. I requested

the mate of the Arran boat and one of the men to take charge of the helm while

I went forward to see that the tug was kept clear of the rocks. Being forward,

I did not see the lifeboat capsise. After the lifeboat capsised, I came aft

and said we should go on slow, because we were so close to shore there was no

need to stop. The boat did not come right and we towed her into the harbour

bottom up, the men clinging to her. The sea was extraordinary heavy in the early

part of the morning. Another eye witness says: At a quarter past seven in the

morning, during the prevalence of a gale from the south-west, I noticed the

boats that went out to the wreck to leeward of the island. They were then making

for the harbour. Everything went well till they were midway between the island

and the pier. Then, as the steamer was about to go to windward of the half-tide

rocks, she drew up to the south-west in order the better to be clear of the

broken water. The lifeboat was then in tow astern and would not answer her helm

very cleverly and so she put her shoulder into the sea - the pilot boat being

still astern - or filled. There was a heavy sea running and much broken water

at the time. This caused her to capsise and the whole of the crew of the lifeboat

and the saved mariners who were in her, were thrown into the water. The men

hung onto her, evidently thinking she would right herself instantly, which should

have been the case with a boat of her class. Under the most adverse circumstances,

everyone scrambled for bare life. Most of the men succeeded in getting hold

of the life lines on her side which run round the boat and succeeded in climbing

onto the keel. In this way, they were towed into the harbour, sometimes more

under than above water. Some of the men holding on to the life lines were coming

in tow of the tug, head down. Two of the men - Brodie and Grier - were found

floating, in their life jackets, by a boat put out from the North Eastern, who

manned that vessels lifeboat and went out and picked up these two men. Brodie

came round but Grier expired shortly after he was taken into the boat. Two of

the sailors, the steward and another man, were lost in the casualty. McEwan

was got floating out from the pier about an hour afterwards. An eye witness

of what transpired overnight, till the close of the catastrophe, says:-About

a quarter past one, on Monday morning, I was awakened by the storm. At that

time it was blowing pretty stiff and I was curious enough to take a look out

of my window which faces the north shore. In and about the harbour, there was

a mixture of red, green and white lights which proved to be those of the brig

Alexandria and the tug. I also observed a white light towards the south end

of the Horse Island. This however, did not excite my attention at the time as

I thought it was that of a steamer going up the Clyde. After watching it for

a short time and not seeing it move, it occurred to me that it might be that

of a vessel on the island. Lifting an opera-glass, I looked towards the light

and could make out the loom of what I took to be a large vessel. I did not then

think of going out and returned to bed. I did not sleep, however, but watched

the light and about two o'clock observed two flash lights and then saw the tug

go out. I could not rest, so got up, dressed and went out. As I past the slip

at the fish market, I observed the carriage of the lifeboat in the water and

knew that she had gone out. When I got down to the Arran boat's berth, the tug

had just come in. The crew, on being questioned, said they had heard voices

on the island and supposed they cried out, "All right". They had a

doubt to this however. The master of the tug, who had got his face badly cut

by the towing hauser of the lifeboat, went home to have it dressed. It was deemed

necessary that the tug should go out again as soon as he had had this operation

performed as no sign from the lifeboat had been obtained for a considerable

time and it was feared she might have come to grief among the rocks. In the

interval, one of the coastguardsmen was dispatched to send up a rocket and a

blue light was burned at the Pilot-house. Neither of these signals was answered.

The master of the tug having returned, her lines were let go and she steamed

out. This would be about four o'clock. As she passed the old pier, a very heavy

squall came away. I think it blew then and for half an hour afterwards, harder

than at any other part of the night. The tug proceeded round the island by the

south end and 'came to' off the north end. In reply to her steam whistle, a

lantern was shown from the north end and two blue lights were burned from the

'spire.' The tug then returned on the same course as she had gone out. She came

into berth and the crew reported. They had heard nothing. They were of opinion,

though, that the ship's crew had not yet got ashore. This conjecture afterwards

proved correct. It was then suggested and agreed to that the tug should tow

out the pilot, or some other boat and that men should go on board the tug to

row the boat ashore, when they reached quiet water. The tug had to be coaled

first, both as the coals were needed and also for ballast, as the master was

afraid she mightcapsize, she being so light. The coaling took up a considerable

time and it was about half past six ere she was in trim for starting again.

She left the harbour about a quarter to seven with the pilot boat in tow and

proceeded inside the Crinan Rock to the north end of the island. Having got

into comparatively smooth water, four men got into the pilot boat and rowed

ashore. A considerable crowd had by this time collected on the old pier and

the proceedings were watched with intense interest. The crew of the ship had

just been landed on the island and they along with the lifeboat crew, proceeded

towards that part of the beach where the pilot boat had gone in and where the

lifeboat also lay at anchor. About a quarter past seven, the pilot boat pulled

off to the tug and her hands were taken on board. She was closely followed by

the lifeboat and the tug having passed a hawser on board she was taken in tow,

the pilot boat being astern of her. The tug went towards the south for three

or four hundred yards and then put about and stood in towards the Long Craigs,

for about the same distance, when she was headed for the harbour. Meantime the

lifeboat and pilot boat had been following her all right and remarks were made

on the quay how well the former was behaving. When the tug, however was for

the harbour, she would not follow, her rudder being seemingly useless, as she

was going along on the crest of a large wave, I was afraid at one time that

she was to be dashed against the tug. Having sunk in the hollow of a wave, her

rudder seemed to take effect and she was coming round. Just as she was doing

so, another wave caught her and carried her to leeward and her hawser tightening

and the next wave, a broken one, catching her on the quarter just at that moment,

in an instant, she was overturned and all on board were thrown into the water.

The tug had stopped and this gave the men an opportunity of laying hold of the

lifeboat, which remained bottom up. Three poor fellows had, however dropped

astern and those on board the tug, seeing they could do nothing to assist them,

did in my opinion, the best thing they could have done, namely steamed ahead.

So sudden had been the catastrophe, that those on the pier for a moment did

not seem to realise it. When they did, the excitement was beyond bounds. The

wives of the lifeboat men who had come on the pier wrung their hands in grief

and the crowd showed their sympathy by using all the means available, which

alas, were few, to rescue the drowning men. A lifeboat was promptly launched

from the North Eastern and five brave men - Mr Charles Adair, pilot along with

Messrs Bell, Todd, Arthur Spencer, Henry Cope and George Fergusson, the second

mate - pulled out to lend what aid they could.  I

saw them pick up one man and the lifeboat, having passed into the harbour, I

waited no longer, but went along the shore thinking I might be of assistance

if any of the men whom I had seen in the water came ashore alive. I was closely

followed by a number of men. I proceeded to the Long Craigs (shown right in

2010) and on looking back saw a man struggling in the water, waving his hand.

This man I think was McEwen. Two men were up to the neck, expecting him to come

within their reach as he was only a short distance from them. Although they

had been swimmers, it would have been madness on their part, in my opinion,

to have tried to reach him by swimming, so heavy was the surf. I went along

the water line the full length of the Long Craigs, but saw nothing. When I came

back the man I had seen in the water had disappeared from my view. He had probably

been carried outwards by the tide, which at the time was ebbing. I went home

about half past eight, having spent a night full of excitement. Charles Reid,

second mate of the Matilda Hillyards, says, in his narrative: The pilot says

he saw the ship coming. I replied "Then why did you not come out?".

He said he thought we were coming into the harbour. Then he saw us put the helm

hard a-starboard and knew we were getting on the lea shore. When the vessel

had gone ashore, he went to the harbour-master and reported to him and those

on board the tug boat, that the ship was ashore. At that time, we on the vessel

made fire and blue lights but had no answer. The ship was labouring heavily

all this time. After about two hours had passed we got an answer. Then a steam

tug came out with the lifeboats and all they did for a time was to halloo. It

was not dangerous for them at this time to come alongside of us. No boat came.

The captain then said "We will stick to the ship." and we took his

advice. At this time a very heavy storm came on, so that no one could come out

to us. Then we heard a noise from the island that we could not understand. The

ship all the while, laboured heavily and the men suffered a good deal. As she

was 'bumping' and in bad condition, we were thrown about very much. In the morning

we went ashore on 'the line.' We had two apparatus on deck for signalling and

also a gallon and a half of paraffin oil. We were obliged to leave a line on

the island, as they had made no preparations for taking us ashore. We hove a

line to them to make fast and we held it tight aboard. They had a 'pluck' on

to hold the men and a line to pull them ashore. Two of the crew were the first

to land, the second mate was the next and when he (the narrator) set foot on

it, he thought it was a glorious haven and thanked God for it. The remainder

of the crew and the captain came ashore afterwards. We were then all on the

island. At daybreak we were told to get into the lifeboat and at once did so.

When in the lifeboat, I thought to myself that there were too many in it. Then

looking at the sea before us, I spoke to the chief mate on the subject and he

said all was right. We were soon alongside the tug. He took us in tow. Now there

was a big sea ahead of us and breakers. The boat went very fast and every sea

that came, she went right bow under and I expected every moment she was to be

foundered. The captain said the wheel could not keep us straight. He asked for

help and I rendered him assistance. All the crew were shouting at him. After

we got so far abreast of the Old Harbour, the steamboat went right across us,

broadside to the sea and brought the lifeboat to one side and then to the other

side of the tow rope and so capsized the lifeboat and we were all thrown into

the sea. I then got hold of the gunwale and the stern sheets. One of the lifeboatmen

got hold of me by the neck and held me up for five minutes, till I begged him

for God's sake to let me go. The sea was washing heavily over me and my hands

and body, from the waist down to my extremities, were so benumbed that I begged

him for God' sake to let me go. I kept my head collected and saw that the steamer

was towing fast on. I was glad when we came to the harbour. There everybody

was picked up. I was taken charge of by two men who brought me to the Eglinton

Arms Hotel where I soon recovered and in about four hours I was myself again.

Mr Charles Adair, on seeing what danger the lifeboat was in, jumped on board

the North Eastern and with the assistance of Robert Todd, the knocking away

her 'chops' and getting that ship's lifeboat afloat was the work of a minute.

These two were accompanied by the mate of the steamer Mr Bell, at one time mate

of the barque Jessie Goodwin and Arthur Spencer, Henry Cope and George Fergusson,

the mate of the steamship. Five minutes after the Fair Maid had capsized, they

were round the pier and made diligent search for any bodies that might be in

the water. We kept out towards the boat, those on the pier-head making signs

to us what course to steer. I saw Brodie in the water, hailed him and bade him

keep up as we would soon be at him. He was motionless when I got hold of him

but, with the assistance of another man, he was soon got into the bottom of

the boat. But for the oar, which Brodie clung to and which kept his head above

water, it is believed he would have perished before he was rescued from peril.

We saw another man, some distance off, lying head down and shoulders above water.

This turned out to be William Grier. I laid hold of him and drew him up. On

getting his head above water, I lifted his hand onto the gunwale of the boat

and said "Willie". He made no reply. I then looked into his face.

His eyes were staring and still. I kept his head up, thinking there was life

in him. But on getting the body aboard we found he was dead. We then 'tacked'

in. On going out again, this time with R Todd, George Fergusson, Henry Cope,

Arthur Spencer, Isaac Venas and J Lowrie, we searched for a man who was said

to have been seen going towards the beach but we found the object mentioned

to be a cask. We then made a search for McEwen. While the tide was washing his

body out, the surf setting in swept him into the Old Harbour. Life was gone

before we met in with him. Adair, who was the oldest man in the boat, says the

Belfast men did well, the conduct of the mate being beyond all praise. Todd's

conduct and extreme handiness was encouraging. All throughout the search none

of the hands spoke above their breath. On Tuesday afternoon, Lieutenant Monteith,

Inspector of the Coast Guard force, inspected the lifeboat, and, we understand,

pronounced her seaworthy. As his report is not yet made known, it may be well

to reserve any opinion regarding the Fair Maid.' We know however that she is

regarded with suspicion by local oarsmen who have sat in her and some little

expression of opinion was heard as to her qualities outside the circle of examiners

by those who say they know her. The experiments took place at the steamboat

pier at time of high water. Along with the Inspector were the Honorable Greville

Richard Vernon, Lord Eglinton's Commissioner; Commander Boyle, R N; Captain

McHardy and a number of townsmen. A rope was put under the boat and she was

raised three times by block and tackle and when fairly keel upmost, the rope

was disconnected from the crane chain and she seemed to 'sulk' a little and

then righted. In the one instance, she did so in twenty and in the others, in

from thirty to thirty-five seconds. A very little, one remarked, would have

induced her to 'lie still' as she was. We have kindly been furnished with the

names of the crew of the ill-fated barque. They are George Anderson; Captain

Leytonstowe, Essex; W Herity, Boston, United States; mate Charles Reed, London;

second mate John S Hickey, Norwich, Nova Scotia; cook and steward (drowned);

Frank Astelfoni, Hamburg, A B; Vincent Luthemburger, Vienna, A B, (drowned);

Mark Rubberson, AB; Charles Cele, Norway, A B; Neils Jorgensen, Denmark, A B;

Francis Liddle, Cape Town, A B; Peter Johnson, Norway, A.B; Albert Finger, German,

A B. The lifeboat crew

were William Breckenridge, coxswain, Edward Moloy, James Leitch, James Findlay,

John Templeton, William Grier, Alexander McEwen, Alexander Brodie, James Gillies,

Robert McMurtrie, Hugh Crawford, William Robertson, Patrick Doran. The assiduous

attention that was paid to the shipwrecked men by Drs Robertson, Gaff and Allan

as they were brought ashore, is worthy of very special notice. These gentlemen

did there utmost to allay the sufferings of the most exhausted of the rescued

men. At a meeting of the local branch of the lifeboat association, held on Tuesday

night, a subscription list was opened on behalf of the bereaved families. The

Earl of Eglinton has headed the list with a subscription of £50. The unceasing

vigilance which was exercised by Mr John Craig, shipping agent, is deserving

the highest commendation. He had his hands full night and day, directing operations

ashore and attending to the comfort of the shipwrecked mariners. Mr Hugh Hogarth,

ship chandler and the Captain of the Reformer rendered good service. The funeral

of William Grier and Alexander McEwen took place on Wednesday at half past one

and, as both resided in Harbour Lane (shown below left as Herald Street in 2002)

and within a few doors of each other, the two companies were united. Long before

the mournful cortege moved off, large groups of sympathising friends had gathered

in the immediate neighbourhood and as the two hearses slowly took their departure,

these were largely multiplied, the countenances of both young and old telling

how intensely they were moved at the sight. A large concourse followed the remains

to the Ardrossan Cemetery (shown below centre in 2011) and among others we observed

Lieutenant Montieth, Royal Navy, Inspector of lifeboats; Mr John Craig, honorary

secretary to the National Lifeboat Institution, all the ministers of the town

and a large number of its most respectable inhabitants and merchants. Conspicuous

among those, too, were the surviving crew of the ill-fated barque, with the

Captain, all of whom were paying their last mark of respect for those who had

lost their lives through assisting to save those of the wrecked. As the mournful

pageant passed up Glasgow Street (shown below right in the early 1900s), the

doors and windows of the shops and houses were filled with spectators, all evincing

how deeply they felt. The cemetery was at length reached and dust committed

to dust and as we took our departure we inwardly mused over the chequered career

of the life of our two departed friends, who after braving successfully many

a stormy sea and 'life's fitful fever o'er,' now 'sleep well.' At the suggestion

of the Lifeboat Association, a subscription on behalf of the bereaved families

has been opened, which from the melancholy circumstances of the bereavement,

we hope will be liberally responded to.

I

saw them pick up one man and the lifeboat, having passed into the harbour, I

waited no longer, but went along the shore thinking I might be of assistance

if any of the men whom I had seen in the water came ashore alive. I was closely

followed by a number of men. I proceeded to the Long Craigs (shown right in

2010) and on looking back saw a man struggling in the water, waving his hand.

This man I think was McEwen. Two men were up to the neck, expecting him to come

within their reach as he was only a short distance from them. Although they

had been swimmers, it would have been madness on their part, in my opinion,

to have tried to reach him by swimming, so heavy was the surf. I went along

the water line the full length of the Long Craigs, but saw nothing. When I came

back the man I had seen in the water had disappeared from my view. He had probably

been carried outwards by the tide, which at the time was ebbing. I went home

about half past eight, having spent a night full of excitement. Charles Reid,

second mate of the Matilda Hillyards, says, in his narrative: The pilot says

he saw the ship coming. I replied "Then why did you not come out?".

He said he thought we were coming into the harbour. Then he saw us put the helm

hard a-starboard and knew we were getting on the lea shore. When the vessel

had gone ashore, he went to the harbour-master and reported to him and those

on board the tug boat, that the ship was ashore. At that time, we on the vessel

made fire and blue lights but had no answer. The ship was labouring heavily

all this time. After about two hours had passed we got an answer. Then a steam

tug came out with the lifeboats and all they did for a time was to halloo. It

was not dangerous for them at this time to come alongside of us. No boat came.

The captain then said "We will stick to the ship." and we took his

advice. At this time a very heavy storm came on, so that no one could come out

to us. Then we heard a noise from the island that we could not understand. The

ship all the while, laboured heavily and the men suffered a good deal. As she

was 'bumping' and in bad condition, we were thrown about very much. In the morning

we went ashore on 'the line.' We had two apparatus on deck for signalling and

also a gallon and a half of paraffin oil. We were obliged to leave a line on

the island, as they had made no preparations for taking us ashore. We hove a

line to them to make fast and we held it tight aboard. They had a 'pluck' on

to hold the men and a line to pull them ashore. Two of the crew were the first

to land, the second mate was the next and when he (the narrator) set foot on

it, he thought it was a glorious haven and thanked God for it. The remainder

of the crew and the captain came ashore afterwards. We were then all on the

island. At daybreak we were told to get into the lifeboat and at once did so.

When in the lifeboat, I thought to myself that there were too many in it. Then

looking at the sea before us, I spoke to the chief mate on the subject and he

said all was right. We were soon alongside the tug. He took us in tow. Now there

was a big sea ahead of us and breakers. The boat went very fast and every sea

that came, she went right bow under and I expected every moment she was to be

foundered. The captain said the wheel could not keep us straight. He asked for

help and I rendered him assistance. All the crew were shouting at him. After

we got so far abreast of the Old Harbour, the steamboat went right across us,

broadside to the sea and brought the lifeboat to one side and then to the other

side of the tow rope and so capsized the lifeboat and we were all thrown into

the sea. I then got hold of the gunwale and the stern sheets. One of the lifeboatmen

got hold of me by the neck and held me up for five minutes, till I begged him

for God's sake to let me go. The sea was washing heavily over me and my hands

and body, from the waist down to my extremities, were so benumbed that I begged

him for God' sake to let me go. I kept my head collected and saw that the steamer

was towing fast on. I was glad when we came to the harbour. There everybody

was picked up. I was taken charge of by two men who brought me to the Eglinton

Arms Hotel where I soon recovered and in about four hours I was myself again.

Mr Charles Adair, on seeing what danger the lifeboat was in, jumped on board

the North Eastern and with the assistance of Robert Todd, the knocking away

her 'chops' and getting that ship's lifeboat afloat was the work of a minute.

These two were accompanied by the mate of the steamer Mr Bell, at one time mate

of the barque Jessie Goodwin and Arthur Spencer, Henry Cope and George Fergusson,

the mate of the steamship. Five minutes after the Fair Maid had capsized, they

were round the pier and made diligent search for any bodies that might be in

the water. We kept out towards the boat, those on the pier-head making signs

to us what course to steer. I saw Brodie in the water, hailed him and bade him

keep up as we would soon be at him. He was motionless when I got hold of him

but, with the assistance of another man, he was soon got into the bottom of

the boat. But for the oar, which Brodie clung to and which kept his head above

water, it is believed he would have perished before he was rescued from peril.

We saw another man, some distance off, lying head down and shoulders above water.

This turned out to be William Grier. I laid hold of him and drew him up. On

getting his head above water, I lifted his hand onto the gunwale of the boat

and said "Willie". He made no reply. I then looked into his face.

His eyes were staring and still. I kept his head up, thinking there was life

in him. But on getting the body aboard we found he was dead. We then 'tacked'

in. On going out again, this time with R Todd, George Fergusson, Henry Cope,

Arthur Spencer, Isaac Venas and J Lowrie, we searched for a man who was said

to have been seen going towards the beach but we found the object mentioned

to be a cask. We then made a search for McEwen. While the tide was washing his

body out, the surf setting in swept him into the Old Harbour. Life was gone

before we met in with him. Adair, who was the oldest man in the boat, says the

Belfast men did well, the conduct of the mate being beyond all praise. Todd's

conduct and extreme handiness was encouraging. All throughout the search none

of the hands spoke above their breath. On Tuesday afternoon, Lieutenant Monteith,

Inspector of the Coast Guard force, inspected the lifeboat, and, we understand,

pronounced her seaworthy. As his report is not yet made known, it may be well

to reserve any opinion regarding the Fair Maid.' We know however that she is

regarded with suspicion by local oarsmen who have sat in her and some little

expression of opinion was heard as to her qualities outside the circle of examiners

by those who say they know her. The experiments took place at the steamboat

pier at time of high water. Along with the Inspector were the Honorable Greville

Richard Vernon, Lord Eglinton's Commissioner; Commander Boyle, R N; Captain

McHardy and a number of townsmen. A rope was put under the boat and she was

raised three times by block and tackle and when fairly keel upmost, the rope

was disconnected from the crane chain and she seemed to 'sulk' a little and

then righted. In the one instance, she did so in twenty and in the others, in

from thirty to thirty-five seconds. A very little, one remarked, would have

induced her to 'lie still' as she was. We have kindly been furnished with the

names of the crew of the ill-fated barque. They are George Anderson; Captain

Leytonstowe, Essex; W Herity, Boston, United States; mate Charles Reed, London;

second mate John S Hickey, Norwich, Nova Scotia; cook and steward (drowned);

Frank Astelfoni, Hamburg, A B; Vincent Luthemburger, Vienna, A B, (drowned);

Mark Rubberson, AB; Charles Cele, Norway, A B; Neils Jorgensen, Denmark, A B;

Francis Liddle, Cape Town, A B; Peter Johnson, Norway, A.B; Albert Finger, German,

A B. The lifeboat crew

were William Breckenridge, coxswain, Edward Moloy, James Leitch, James Findlay,

John Templeton, William Grier, Alexander McEwen, Alexander Brodie, James Gillies,

Robert McMurtrie, Hugh Crawford, William Robertson, Patrick Doran. The assiduous

attention that was paid to the shipwrecked men by Drs Robertson, Gaff and Allan

as they were brought ashore, is worthy of very special notice. These gentlemen

did there utmost to allay the sufferings of the most exhausted of the rescued

men. At a meeting of the local branch of the lifeboat association, held on Tuesday

night, a subscription list was opened on behalf of the bereaved families. The

Earl of Eglinton has headed the list with a subscription of £50. The unceasing

vigilance which was exercised by Mr John Craig, shipping agent, is deserving

the highest commendation. He had his hands full night and day, directing operations

ashore and attending to the comfort of the shipwrecked mariners. Mr Hugh Hogarth,

ship chandler and the Captain of the Reformer rendered good service. The funeral

of William Grier and Alexander McEwen took place on Wednesday at half past one

and, as both resided in Harbour Lane (shown below left as Herald Street in 2002)

and within a few doors of each other, the two companies were united. Long before

the mournful cortege moved off, large groups of sympathising friends had gathered

in the immediate neighbourhood and as the two hearses slowly took their departure,

these were largely multiplied, the countenances of both young and old telling

how intensely they were moved at the sight. A large concourse followed the remains

to the Ardrossan Cemetery (shown below centre in 2011) and among others we observed

Lieutenant Montieth, Royal Navy, Inspector of lifeboats; Mr John Craig, honorary

secretary to the National Lifeboat Institution, all the ministers of the town

and a large number of its most respectable inhabitants and merchants. Conspicuous

among those, too, were the surviving crew of the ill-fated barque, with the

Captain, all of whom were paying their last mark of respect for those who had

lost their lives through assisting to save those of the wrecked. As the mournful

pageant passed up Glasgow Street (shown below right in the early 1900s), the

doors and windows of the shops and houses were filled with spectators, all evincing

how deeply they felt. The cemetery was at length reached and dust committed

to dust and as we took our departure we inwardly mused over the chequered career

of the life of our two departed friends, who after braving successfully many

a stormy sea and 'life's fitful fever o'er,' now 'sleep well.' At the suggestion

of the Lifeboat Association, a subscription on behalf of the bereaved families

has been opened, which from the melancholy circumstances of the bereavement,

we hope will be liberally responded to.[We will be pleased to receive and hand over to the Treasurer of the fund any donations our readers may send. - Editor]

Ardrossan and Saltcoats Herald, 6 March 1880

Last

week we briefly noticed the decease of William Breckenridge, one of the crew

of the lifeboat which went out for the crew of the barque, Matilda Hillyards

on 1 March. Breckenridge's first recorded service in the Ardrossan lifeboat

was on 25 November 1873 assisting the crew of the boat Torrance ashore. The

record of that accident bears that he had previously acted four times as a lifeboat

man. Since then, he has been out in the boat on every occasion of service, memorably

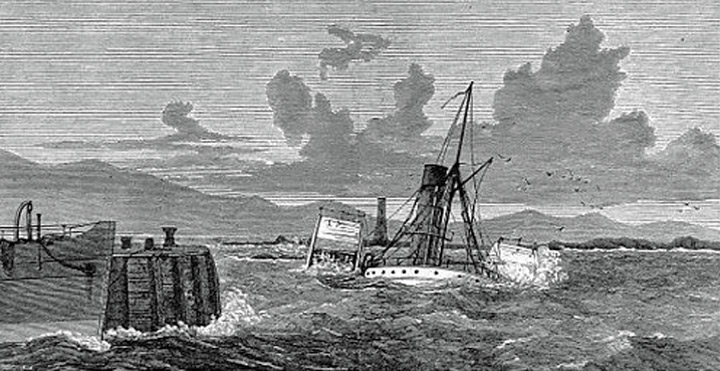

at that of the Chusan (shown right in a print reproduced by kind permission

of the copyright holders Illustrated London News / Mary Evans Picture Library

and available from

Last

week we briefly noticed the decease of William Breckenridge, one of the crew

of the lifeboat which went out for the crew of the barque, Matilda Hillyards

on 1 March. Breckenridge's first recorded service in the Ardrossan lifeboat

was on 25 November 1873 assisting the crew of the boat Torrance ashore. The

record of that accident bears that he had previously acted four times as a lifeboat

man. Since then, he has been out in the boat on every occasion of service, memorably

at that of the Chusan (shown right in a print reproduced by kind permission

of the copyright holders Illustrated London News / Mary Evans Picture Library

and available from