NON-FOOTBALL

STORIES 1874

While looking through old documents, it is almost inevitable that the reader's

attention will be drawn from the intended target to other articles. The reports

below were found in old Ardrossan and Saltcoats Heralds. Although they have

no football content, they may be of interest.

BIRTHS, MARRIAGES AND DEATHS

Mr Hugh Willock, Registrar for New Ardrossan,

gives the number for his district as follows.

1872

1873

Births

149 155

Marriages 22

32

Deaths

79 85

Of the thirty-two deaths registered, sixteen or one-half were upwards of sixty

years of age which is surely a large proportion and indicative of the longevity

of the community. Marriages in New Ardrossan in 1873 were Church of Scotland

- 16, Free - 17, United Presbyterian - 5, Independent - 4. During part of the

year there was no United Presbyterian minister.

Ardrossan and Saltcoats Herald, 3 January

1874

EARLY SNOWDROPS

At Seafield Tower (shown below as Quarriers in 2008), Ardrossan, the residence

of W G Borron, esquire, snowdrops were in bloom on 2 January. As a further proof

of the mildness of the season, March violets are also in bloom at Seafield Tower.

Ardrossan

and Saltcoats Herald,

10 January 1874

LETTER TO THE EDITOR - DARK

STREETS

Would you kindly inform me who is responsible for the lighting of the streets

of Ardrossan? On Sunday night, there was not a lamp lighted in the Crescent

(shown below as South Crescent in the early 1900s) or Princes Street and only

a solitary one in Glasgow Street. While passing along Princes Street about ten

o'clock, I found a respectable man groping about in the dark trying to find

his hat which had been blown off but which, owing to the darkness, he could

not find. Now, Sir, this is not the first time such a thing has happened in

our town this winter and it says a great deal for the conduct of a seafaring

town that it has not been attended with very serious consequences. I think the

attention of the powers-that-be should be called to this matter.

I am, Sir,

Yours most respectively,

A Householder

Ardrossan

and Saltcoats Herald,

24 January 1874

NEW BUILDING COMPANY IN ARDROSSAN

It is proposed to establish in Ardrossan a building company with the view of

increasing house accommodation and enabling parties desirous of acquiring property

of doing so under favourable conditions. We hope, in the course of a week or

two, to have the opportunity of explaining more fully the proposals of the proposed

company.

Ardrossan

and Saltcoats Herald,

2 May 1874

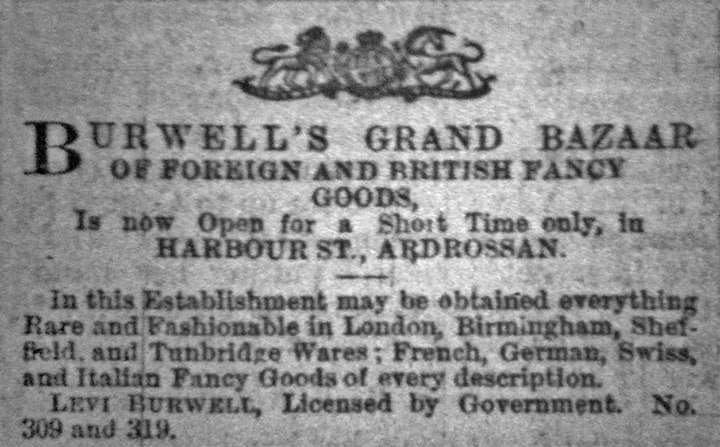

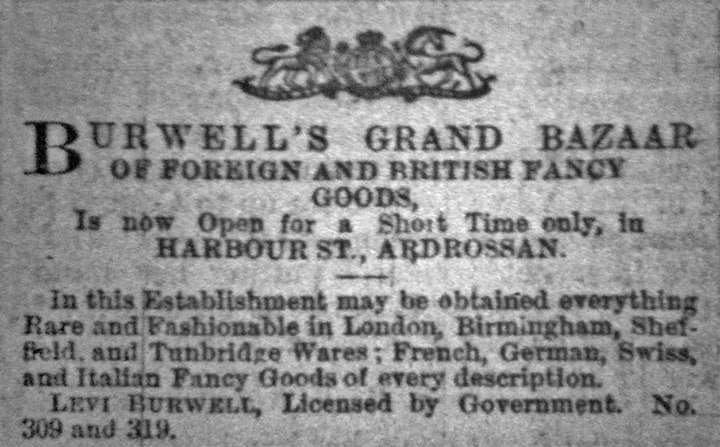

BURWELL'S BAZAAR

It will be seen from the advertisement (shown below), that this old established

bazaar is just now in Ardrossan at the market place where it will be for a short

time. We took a run through it the other evening and were quite delighted with

the beautiful display of everything rich and rare. Then there are the attractions

of the lottery at which fortunes are often lost and won and which we are assured

contains all prizes and no blanks. During our visit, we saw drawn a number of

knick-knacks, Japanese fans, meerschaum pipes, finger rings, big dolls and ladies'

workboxes. The bazaar is well worth a visit.

Ardrossan

and Saltcoats Herald,

6 June 1874

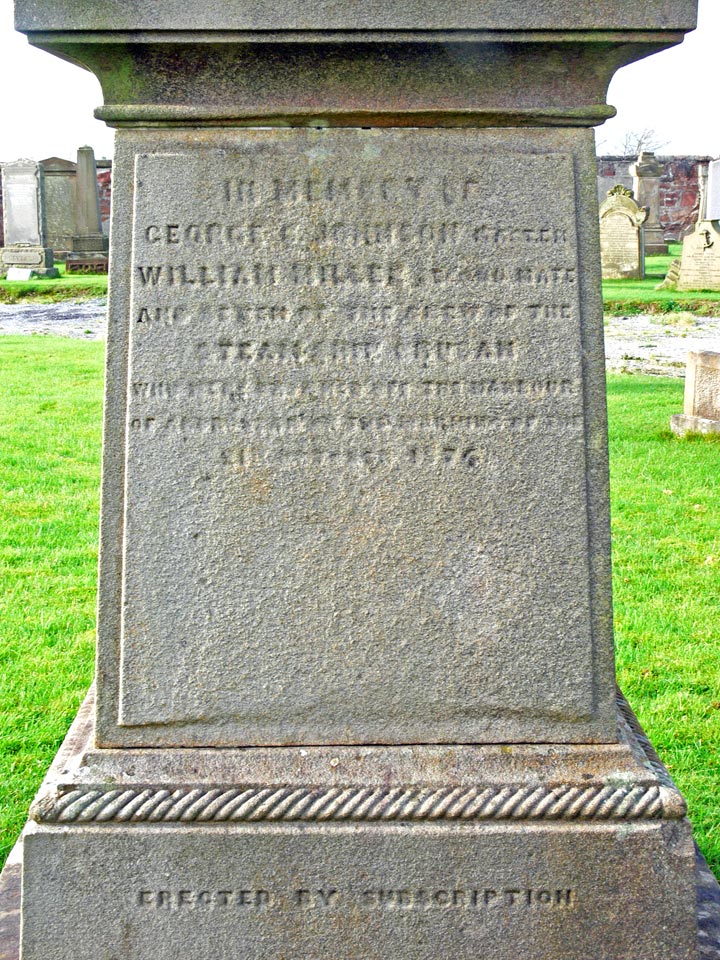

ARDROSSAN CEMETERY

Since the cemetery (shown below in 2010) has been taken over by the Parochial

Board, very considerable improvements have been effected. The half formerly

in crop has been laid off and the and the back premises of the gatekeeper's

house have been enclosed. The cemetery is in fine order, almost every grave

having flowers in bloom. Other improvements might, at little cost, be effected

such as the planting of a few more shrubs where they could find the protection

of gravestones but, as it is, it is very creditable to the taste of the keeper

and we do not wonder that so many visit it.

Ardrossan

and Saltcoats Herald,

6 June 1874

ARDROSSAN REGATTA AND LAND

SPORTS

This regatta and land sports has once again been revived after being in abeyance

for some years and came off on Saturday last (30 August 1974) with great eclat.

Work was very generally suspended and the town wore a holiday aspect which was

more marked in the after part of the day and after the sports when large numbers

patronised the varied sites and amusements spread for their gratification on

The Inches (shown below left in 2003). The weather in the morning was unpromising

but cleared up early in the day and the large number of interested spectators,

many from a distance, that turned out to witness the several events must have

been proof, if that were wanting, of the popularity of such aquatic and land

sports. The varied arrangements, especially those relating to the regatta, were

carried out in an efficient manner and with a promptitude worthy of remark.

The Commodore's barge was anchored outside of Montgomerie Pier and the course

for rowing boats was round a buoy situated near the Horse Island (shown below

centre in 2011) and from thence to the Long Craigs (shown below right in 2010),

the winning point being at the Commodore's barge. The sailing course was twice

round the Horse Island. The spectators had a good view of the course from both

piers. Owing to the freshness of the breeze, it took careful management on the

part of the crews of the racing jolly-boats to tide over the broken water between

the barge and the outmost buoy which was in the vicinity of the Horse Isle.

Mr Barbour as Commodore and Mr Hepburn, secretary, along with the committee,

did their duties in a manner that reflected much credit upon them and which

went far to make this revival of the Ardrossan Regatta a most successful affair.

Ardrossan

and Saltcoats Herald,

5 September 1874

ARDROSSAN TO WEST KILBRIDE

RAILWAY

The new railway works between Ardrossan and West Kilbride are proceeding. Ground

has been broken on the face of the hill on Montfode and Boydston Farms near

to Ann's Lodge. We hear that after harvest, a larger number of navvies will

be employed and the work prosecuted with more vigour.

Ardrossan

and Saltcoats Herald,

19 September 1874

FAST DAY

Wednesday first (30 September 1874) in Ardrossan and neighbourhood will be observed

as a fast day preparatory to the Autumn Sacrament which will be observed in

all the churches on the Sunday following (4 October 1874).

Ardrossan

and Saltcoats Herald,

26 September 1874

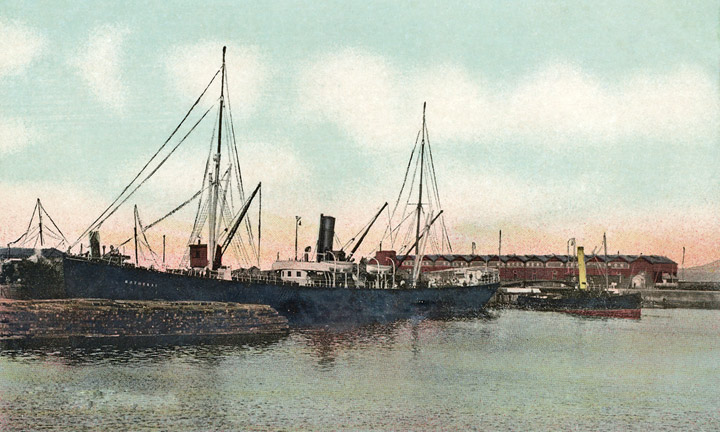

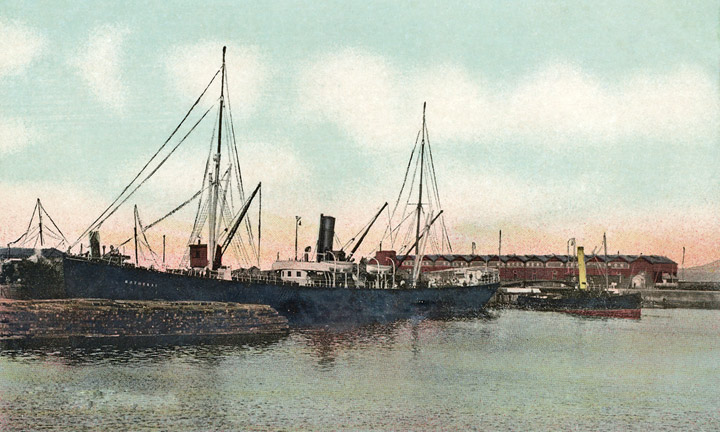

ROBBERY ON SHIPBOARD AT ARDROSSAN

HARBOUR

Early on Friday morning last (9 October 1874), a robbery was discovered to have

been perpetrated on board the ship Jane Young lying in Ardrossan Harbour (shown

below in the early 1900s). Late on Thursday night (8 October 1874), a slight

noise was heard on deck but nothing to create alarm but next morning, it was

discovered that a number of articles, including a quantity of seamen's clothing,

had been stolen. Two men who are a-missing are suspected and the hue-and-cry

being out against them, it is expected that their apprehension will be accomplished

soon.

Ardrossan

and Saltcoats Herald, 17 October 1874

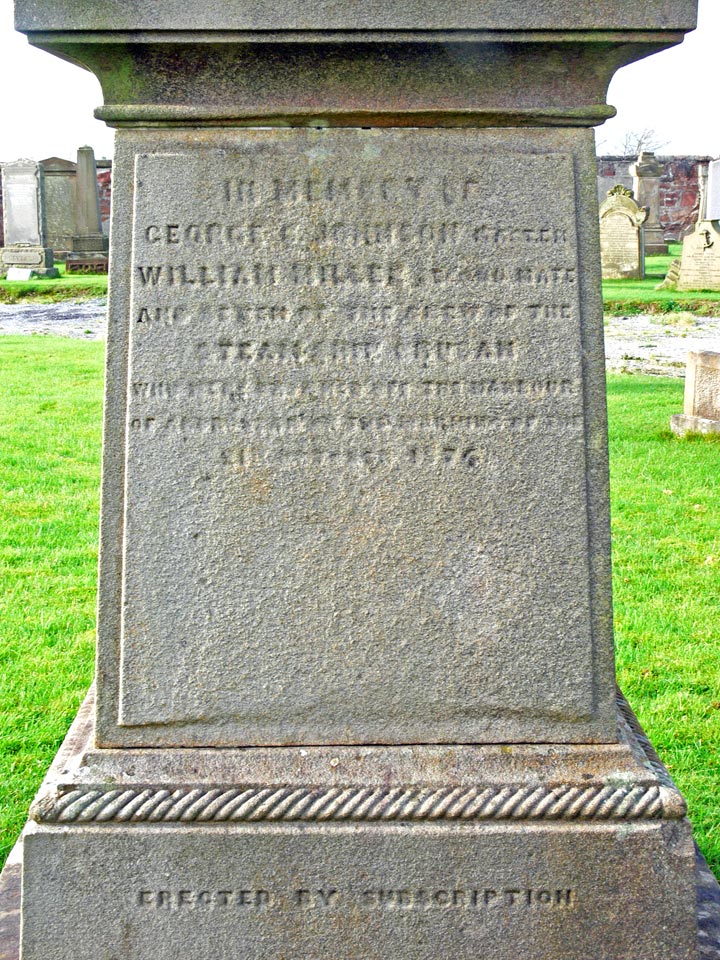

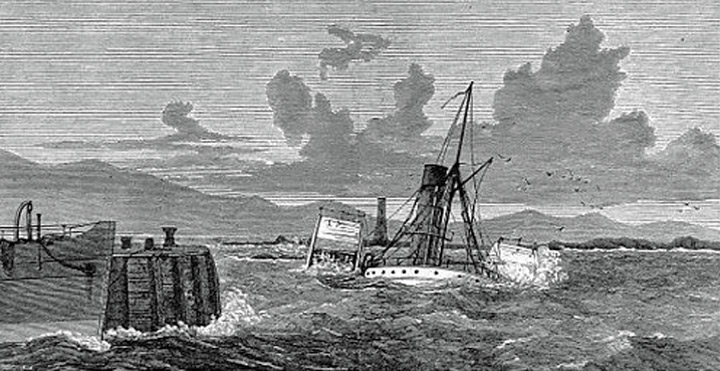

TERRIBLE SHIPWRECK AT ARDROSSAN HARBOUR

One of the most appalling shipwrecks which ever occurred on this coast took

place at Ardrossan on Wednesday morning (21 October 1874) so close to the harbour

that it was distinctly witnessed by hundreds of horrified spectators from both

piers. The ill fated vessel was a new iron paddle steamer from Glasgow for Shanghai

named the Chusan and belonging to the China Steam Navigation Company, the London

agents being Baring Brothers and Company. Her engines were nominally 300 horsepower

and her measurement 3500 40-94th tons; length between perpendiculars - 300 feet;

breadth moulded - 50 feet; breadth over sponsons - 83 feet; depth moulded -

13 feet. She was built by Messrs Elder and Company, Govan and was launched in

September last, her register tonnage being 1000 tons. Of a slender construction,

she was not at all adapted for weathering a heavy gale like that of Wednesday

morning and what was fitted to render her behaviour in such a storm of the less

seaworthy was that, after the fashion of American riverboats, she had a beam-engine

on deck. She was manned by a crew of forty-eight all told comprising engineers,

firemen, etc and had the channel pilot, Mr Moir, on board and one passenger,

Captain King, who was on his way to take the command of one of the same company's

steamers in China. The Chusan was under the command of Captain Johnson whose

wife and child of four years of age were on board with him. His wife's sister

was also on board in the capacity, it was stated, of stewardess. She had no

cargo with the exception of about 800 tons of coals to be used on the passage

out and £1000 worth of goods belonging to the captain who intended to

trade on his own account. Thus equipped, she left the Tail of the Bank, Greenock

on Wednesday 10th and got as far as Waterford in Ireland. There, on account

of some inspection of the vessel, she was put back to be strengthened for proceeding

on her voyage and was caught in the gale of Wednesday morning. At about two

o'clock in the morning, the vessel became unmanageable and would not answer

her helm. She was then off Ailsa Craig and the pilot determined to run for the

Cumbraes but could not get her to keep her course direct up channel. The captain

at that time sounded the hold and found it to contain no water. The whole of

the hands were on deck according to the statement of the boatswain, a negro

named Thomas James who had, by the captain's orders, roused the crew at about

half past twelve o'clock. It was found that the vessel had drifted towards the

land and, seeing that they would not be able to make up the channel, it was

resolved to run for Ardrossan harbour. The pilots on the lookout, seeing the

steamer making for the harbour thought it was the Belfast steamer putting back

and went round to the berth it usually occupies in order to get the moorings

ready. When the vessel came closer, however, they discovered their mistake and

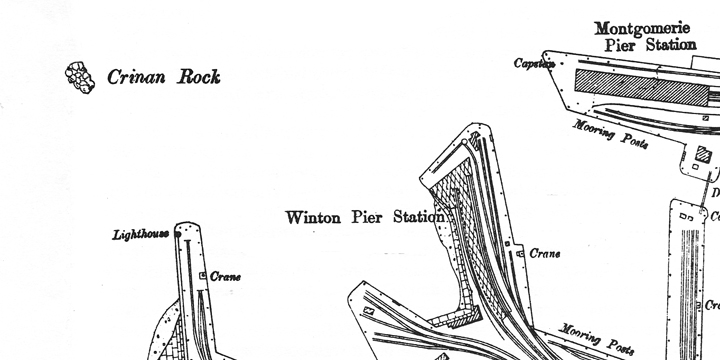

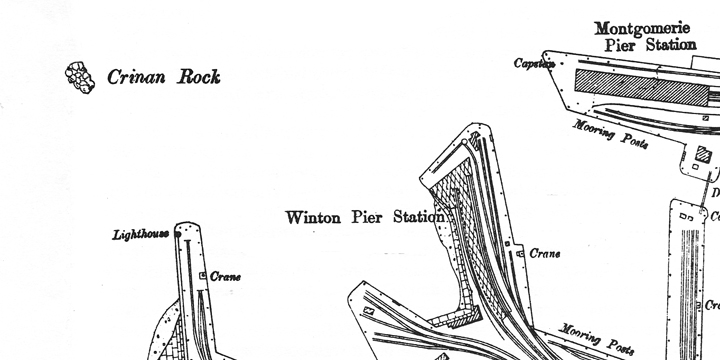

were looking on when she struck on the Crinan Rock  (shown

in the map right before the breakwater was built in the early 1890s) which is

about four hundred yards from the mouth of the harbour and whose presence is

marked by a beacon. Its sides are almost perpendicular and at low tide there

is a depth of eighteen feet alongside. She was making for the harbour well enough

and would have taken in, they allege, but not knowing the harbour and, finding

themselves close on the rock, the engines were reversed and at that time, the

storm getting complete mastery of her, she swung round and struck on the rock

amidships. She struck once and rose on the waves again, struck a second time

and rose but before she could get clear, she was caught in an eddy and striking

a third time, she parted amidships as clean as though she had been sawn right

through. The fires of the engine glared out on the raging sea as the stern half

sank and a scene of indescribable terror and confusion ensued. Part of the bridge

and paddle boxes remained above water and to these and the rigging those on

board clung, the water washing over them and knocking some of them adrift. The

fore part of the vessel, with a number of the crew on board, floated safely

into the old harbour, the ship having been built in watertight compartments.

It was blown right up to the top of the harbour and grounded without doing any

injury to the vessels moored there, settling into the best and safest spot that

could possibly have been selected. Not more than five minutes elapsed between

the time when the vessel struck and the instant she parted and, as soon as the

disaster was witnessed, one of the pilots rushed off to the residence of the

coxswain of the lifeboat where the keys of the lifeboat house are kept. The

house was locked up, Phillips being absent at drill and another set of keys

being in possession of the harbourmaster, Mr Archibald Steel, access was had

to the lifeboat and a crew consisting of one of the pilots and a number of carpenters

was hastily extemporised. The tug, meanwhile, had got her steam up and was alongside

the wreck but the number of men on board were too few to cope with the task

before them. A line was thrown to the wreck and was caught by Captain Johnson

who made it fast to his wife. Seizing hold of it himself, he sprang into the

water along with his wife. The weight was too much. Those on board the tug could

not draw them up and the water kept rushing over them and dashing them against

the paddle box. Captain Johnson put forth every effort to keep his wife's head

above water and at last let go, sinking with his right hand raised and in the

act of pushing his wife towards the tug. The second line thrown from the tug

was caught by the boatswain, Thomas James, a negro, who was hauled on board

the tug and who for several minutes, as far as he could judge, was about three

minutes on board the tug before Captain Johnson's wife was rescued. James says

he had been shipwrecked more than a dozen times and has seen women saved from

wrecked vessels but never saw one who held out so well as did Mrs Johnson. She

was, however, very far gone when rescued. Her state is now regarded as most

favourable, she being near her confinement. The fourth engineer, George Mair,

catching a line twisted it round his arm and was easily hauled up. The first

engineer, Mr William Gardner of Glasgow, however, had a very narrow escape.

He was fresh from the hot engine room and missed the line which was thrown to

him. Though unable to swim, he jumped into the sea and caught hold of it. The

rope was a rather thin one and his hands getting numb, he felt it slipping and

he had almost given up hope but he stuck to it till taken hold off and was dragged

on board the tug. The second engineer, William Ortwin and the third, John Wrench,

were also saved. A number more were picked up and the tug brought them ashore.

Other three were floated on pieces of wreck to the pier-head and were rescued

at the imminent risk of the lives of those who saved them. Some of those who

tried to reach land by means of pieces of wood were carried to sea and lost.

The water was breaking in solid masses over the pier but the Captain of the

Newry steamer Amphion, the pilots and a number of carpenters succeeded in saving

the three who came within reach of the lifebuoys. The captain of the Amphion

hauled one of them up with his own hands and the three were very handsomely

treated on board his vessel. A number, however, who came very near the lifebuoys

were carried past by the back set of the water and, drifting out to sea, were

drowned. The first mate, Mr Johnstone, was saved but the second mate, Mr Miller,

was drowned. On enquiring at the boatswain and engineer as to how he had failed

to catch a line, the other white men on board having done so, we were informed

that neither of them had seen him during the whole time of the disaster, and

one of the crew who was present at this interview, said he saw the second mate

drifting out to sea on a fragment of the wreck. Mr Miller's chest came ashore

in the course of the afternoon and was taken into the pilot house and is now

in the custody of the Collector of Customs. It contained, among other things,

a bank book showing a deposit of £35 at his credit. The most heart-rending

scene of all was the spectacle presented by a poor fellow who got jammed at

the stern of the vessel and the brave attempts to rescue him made by four carpenters

who, notwithstanding the violence of the storm, went out in a boat belonging

to the pig-iron men, deserving of the greatest praise. They got near enough

to speak to the poor fellow and throw him a line but it proved to be of no use.

They then rowed close up and one of them seized him but only succeeded in pulling

the poor fellow's clothes off his shoulders. The sea rose and fell over him

continuously and for more than an hour, he kept his erect position, visible

but for a moment then hid again by a heavy sea. At last, he was seen to fall

on his side and after a long an weary watching for a chance of escape, he was

lost from view altogether. The tug meantime, having returned to the harbour

and towed the lifeboat on to the scene of action and allowed it to drop down

on the weather side. After several attempts, they succeeded in fixing her grapplings

on to the stern of the steamer within a distance of not more than fifteen or

twenty yards of the six persons still clinging to the wreck. Strenuous efforts

were made to get them off. One of the crew had taken refuge in the rigging and

so was not at the mercy of the waves as were those on deck. Miss Elliott, along

with the Captain's child and one of the crew, had a rough time of it on the

main boom of the ship. Having got themselves firmly fixed between the wire rope

and the end of the boom, they maintained their position for nearly an hour,

being swung to and fro clear of the deck of the ship by the great violence of

the waves. For long, the pilot on the bow of the lifeboat tried to cast a line

over them but was for a time unavailing. With every failure, Miss Elliott was

observed motioning with her hand as if signifying the hopelessness of the efforts

that were being made to rescue the sufferers in the face of such a furious storm

and blinding rain from their dreadfully perilous position. At last he succeeded

and one by one the sufferers were drawn through the angry waves and safely lodged

in the lifeboat. It may be mentioned here that twice the child fell into the

water and twice one of the engineers got hold of him and brought him up again.

It was about nine o'clock when the lifeboat came off with the last of the crew

who had upwards of three hours borne their fate gallantly. All save one were

helpless and unconscious on coming ashore. Mr Moir, the channel pilot was taken

off by the lifeboat along with the others, all of whom were drawn through the

sea to the boat by means of a line which was passed round the body of one of

the crew who showed great agility and strove hard and succeeded in doing for

the others what they could not do for themselves when paralysed by fatigue and

cold. All the crew with the exception of the officers and engineers were coloured

men. They received every attention as they came ashore, some of the young men

standing by as they were brought ashore pulling off their jackets and giving

them to the half-drowned men. The steward stripped and swam ashore. He was the

only one of whom we could discover to have accomplished this feat. Dr Stevens

sent them down a suit of clothes and along with Dr Wallace was most attentive

to Mrs Johnson, her child and sister. Captain King, who as we have mentioned

had made up his mind to stick by the wreck was washed against the rail by a

heavy sea and was latterly washed adrift, thereafter caught hold a piece of

wood on which he managed to get ashore. He was hauled on board the tug boat.

The paddle boxes were above water during the whole day and portions of the wreck

kept drifting to the harbour. The scene was visited by thousands during the

day. Yesterday, Friday, it was ascertained that nine lives had been lost. Thursday

last being Glasgow fast day, large numbers from the city visited the scene of

wreck and looked with a melancholy interest on the noble ship which had so lately

left their river, now such a wreck and on the spot where she lay which will

long be remembered as the scene of one of the most heart-rending disasters in

the wreck register of the west coast of Scotland. We may add that Mr Gross,

procurator fiscal, was at Ardrossan on Wednesday and Thursday making investigation

into the whole circumstances of the wreck. Mr Wilde, surveyor to the Underwriters'

Association, will excuse us making any attempt to name those who rendered special

assistance - deeper interest in distressed men and stronger desire to give help

of any kind, whether in food or shelter, could not possibly have been shown

by any community. Mr Steel, harbour master of Ardrossan, states: I was on duty

when the vessel came in sight. I observed that she was in danger and seemed

to stand right to the harbour. I was so convinced of this that I ordered the

men to stand on the pier and they were there ready with heaving lines in case

she should manage to reach the harbour. All at once, the vessel canted or swung

round to the north and afterwards appeared on the other side of the Crinan Rock

which is four hundred yards from the other side of the shore. She was distant

from the rock about half a boat's length. She occupied this position for about

a quarter of and hour after we first noticed her. She was very much stressed.

The only thing we could make out was that her engines were working. We observed

that she reversed her engines and she was backing towards the sea. She continued

backing when the smash occurred. The engines seemed to be still going but at

this point they appeared suddenly to stop. She was contending against the elements

but had not struck the rock at that time. After that, she stuck upon the rock

as it appeared to us. It was grey daylight at that time. She first drifted down,

then her engines stopped then she struck the rock knocking away the post or

beacon which stood there as a signal. There was no light on the rock at the

time. Just as she struck on the rock, a heavy sea came and the fore end of the

vessel rose and she seemed to us to part in two exactly at the middle. The fore

end of her fell clear of the rock coming in and striking the pier. Three of

the men who were on this part of the vessel made an attempt to run for the shore

and two of them succeeded. Those who were on shore cried to the third not to

attempt it as the vessel was then rebounding from the pier and his chances of

getting on shore were correspondingly diminished. They threw lifebuoys and made

every effort to save him but the current was so strong that he was swept out

and lost. There might have been a dozen on the fore part

(shown

in the map right before the breakwater was built in the early 1890s) which is

about four hundred yards from the mouth of the harbour and whose presence is

marked by a beacon. Its sides are almost perpendicular and at low tide there

is a depth of eighteen feet alongside. She was making for the harbour well enough

and would have taken in, they allege, but not knowing the harbour and, finding

themselves close on the rock, the engines were reversed and at that time, the

storm getting complete mastery of her, she swung round and struck on the rock

amidships. She struck once and rose on the waves again, struck a second time

and rose but before she could get clear, she was caught in an eddy and striking

a third time, she parted amidships as clean as though she had been sawn right

through. The fires of the engine glared out on the raging sea as the stern half

sank and a scene of indescribable terror and confusion ensued. Part of the bridge

and paddle boxes remained above water and to these and the rigging those on

board clung, the water washing over them and knocking some of them adrift. The

fore part of the vessel, with a number of the crew on board, floated safely

into the old harbour, the ship having been built in watertight compartments.

It was blown right up to the top of the harbour and grounded without doing any

injury to the vessels moored there, settling into the best and safest spot that

could possibly have been selected. Not more than five minutes elapsed between

the time when the vessel struck and the instant she parted and, as soon as the

disaster was witnessed, one of the pilots rushed off to the residence of the

coxswain of the lifeboat where the keys of the lifeboat house are kept. The

house was locked up, Phillips being absent at drill and another set of keys

being in possession of the harbourmaster, Mr Archibald Steel, access was had

to the lifeboat and a crew consisting of one of the pilots and a number of carpenters

was hastily extemporised. The tug, meanwhile, had got her steam up and was alongside

the wreck but the number of men on board were too few to cope with the task

before them. A line was thrown to the wreck and was caught by Captain Johnson

who made it fast to his wife. Seizing hold of it himself, he sprang into the

water along with his wife. The weight was too much. Those on board the tug could

not draw them up and the water kept rushing over them and dashing them against

the paddle box. Captain Johnson put forth every effort to keep his wife's head

above water and at last let go, sinking with his right hand raised and in the

act of pushing his wife towards the tug. The second line thrown from the tug

was caught by the boatswain, Thomas James, a negro, who was hauled on board

the tug and who for several minutes, as far as he could judge, was about three

minutes on board the tug before Captain Johnson's wife was rescued. James says

he had been shipwrecked more than a dozen times and has seen women saved from

wrecked vessels but never saw one who held out so well as did Mrs Johnson. She

was, however, very far gone when rescued. Her state is now regarded as most

favourable, she being near her confinement. The fourth engineer, George Mair,

catching a line twisted it round his arm and was easily hauled up. The first

engineer, Mr William Gardner of Glasgow, however, had a very narrow escape.

He was fresh from the hot engine room and missed the line which was thrown to

him. Though unable to swim, he jumped into the sea and caught hold of it. The

rope was a rather thin one and his hands getting numb, he felt it slipping and

he had almost given up hope but he stuck to it till taken hold off and was dragged

on board the tug. The second engineer, William Ortwin and the third, John Wrench,

were also saved. A number more were picked up and the tug brought them ashore.

Other three were floated on pieces of wreck to the pier-head and were rescued

at the imminent risk of the lives of those who saved them. Some of those who

tried to reach land by means of pieces of wood were carried to sea and lost.

The water was breaking in solid masses over the pier but the Captain of the

Newry steamer Amphion, the pilots and a number of carpenters succeeded in saving

the three who came within reach of the lifebuoys. The captain of the Amphion

hauled one of them up with his own hands and the three were very handsomely

treated on board his vessel. A number, however, who came very near the lifebuoys

were carried past by the back set of the water and, drifting out to sea, were

drowned. The first mate, Mr Johnstone, was saved but the second mate, Mr Miller,

was drowned. On enquiring at the boatswain and engineer as to how he had failed

to catch a line, the other white men on board having done so, we were informed

that neither of them had seen him during the whole time of the disaster, and

one of the crew who was present at this interview, said he saw the second mate

drifting out to sea on a fragment of the wreck. Mr Miller's chest came ashore

in the course of the afternoon and was taken into the pilot house and is now

in the custody of the Collector of Customs. It contained, among other things,

a bank book showing a deposit of £35 at his credit. The most heart-rending

scene of all was the spectacle presented by a poor fellow who got jammed at

the stern of the vessel and the brave attempts to rescue him made by four carpenters

who, notwithstanding the violence of the storm, went out in a boat belonging

to the pig-iron men, deserving of the greatest praise. They got near enough

to speak to the poor fellow and throw him a line but it proved to be of no use.

They then rowed close up and one of them seized him but only succeeded in pulling

the poor fellow's clothes off his shoulders. The sea rose and fell over him

continuously and for more than an hour, he kept his erect position, visible

but for a moment then hid again by a heavy sea. At last, he was seen to fall

on his side and after a long an weary watching for a chance of escape, he was

lost from view altogether. The tug meantime, having returned to the harbour

and towed the lifeboat on to the scene of action and allowed it to drop down

on the weather side. After several attempts, they succeeded in fixing her grapplings

on to the stern of the steamer within a distance of not more than fifteen or

twenty yards of the six persons still clinging to the wreck. Strenuous efforts

were made to get them off. One of the crew had taken refuge in the rigging and

so was not at the mercy of the waves as were those on deck. Miss Elliott, along

with the Captain's child and one of the crew, had a rough time of it on the

main boom of the ship. Having got themselves firmly fixed between the wire rope

and the end of the boom, they maintained their position for nearly an hour,

being swung to and fro clear of the deck of the ship by the great violence of

the waves. For long, the pilot on the bow of the lifeboat tried to cast a line

over them but was for a time unavailing. With every failure, Miss Elliott was

observed motioning with her hand as if signifying the hopelessness of the efforts

that were being made to rescue the sufferers in the face of such a furious storm

and blinding rain from their dreadfully perilous position. At last he succeeded

and one by one the sufferers were drawn through the angry waves and safely lodged

in the lifeboat. It may be mentioned here that twice the child fell into the

water and twice one of the engineers got hold of him and brought him up again.

It was about nine o'clock when the lifeboat came off with the last of the crew

who had upwards of three hours borne their fate gallantly. All save one were

helpless and unconscious on coming ashore. Mr Moir, the channel pilot was taken

off by the lifeboat along with the others, all of whom were drawn through the

sea to the boat by means of a line which was passed round the body of one of

the crew who showed great agility and strove hard and succeeded in doing for

the others what they could not do for themselves when paralysed by fatigue and

cold. All the crew with the exception of the officers and engineers were coloured

men. They received every attention as they came ashore, some of the young men

standing by as they were brought ashore pulling off their jackets and giving

them to the half-drowned men. The steward stripped and swam ashore. He was the

only one of whom we could discover to have accomplished this feat. Dr Stevens

sent them down a suit of clothes and along with Dr Wallace was most attentive

to Mrs Johnson, her child and sister. Captain King, who as we have mentioned

had made up his mind to stick by the wreck was washed against the rail by a

heavy sea and was latterly washed adrift, thereafter caught hold a piece of

wood on which he managed to get ashore. He was hauled on board the tug boat.

The paddle boxes were above water during the whole day and portions of the wreck

kept drifting to the harbour. The scene was visited by thousands during the

day. Yesterday, Friday, it was ascertained that nine lives had been lost. Thursday

last being Glasgow fast day, large numbers from the city visited the scene of

wreck and looked with a melancholy interest on the noble ship which had so lately

left their river, now such a wreck and on the spot where she lay which will

long be remembered as the scene of one of the most heart-rending disasters in

the wreck register of the west coast of Scotland. We may add that Mr Gross,

procurator fiscal, was at Ardrossan on Wednesday and Thursday making investigation

into the whole circumstances of the wreck. Mr Wilde, surveyor to the Underwriters'

Association, will excuse us making any attempt to name those who rendered special

assistance - deeper interest in distressed men and stronger desire to give help

of any kind, whether in food or shelter, could not possibly have been shown

by any community. Mr Steel, harbour master of Ardrossan, states: I was on duty

when the vessel came in sight. I observed that she was in danger and seemed

to stand right to the harbour. I was so convinced of this that I ordered the

men to stand on the pier and they were there ready with heaving lines in case

she should manage to reach the harbour. All at once, the vessel canted or swung

round to the north and afterwards appeared on the other side of the Crinan Rock

which is four hundred yards from the other side of the shore. She was distant

from the rock about half a boat's length. She occupied this position for about

a quarter of and hour after we first noticed her. She was very much stressed.

The only thing we could make out was that her engines were working. We observed

that she reversed her engines and she was backing towards the sea. She continued

backing when the smash occurred. The engines seemed to be still going but at

this point they appeared suddenly to stop. She was contending against the elements

but had not struck the rock at that time. After that, she stuck upon the rock

as it appeared to us. It was grey daylight at that time. She first drifted down,

then her engines stopped then she struck the rock knocking away the post or

beacon which stood there as a signal. There was no light on the rock at the

time. Just as she struck on the rock, a heavy sea came and the fore end of the

vessel rose and she seemed to us to part in two exactly at the middle. The fore

end of her fell clear of the rock coming in and striking the pier. Three of

the men who were on this part of the vessel made an attempt to run for the shore

and two of them succeeded. Those who were on shore cried to the third not to

attempt it as the vessel was then rebounding from the pier and his chances of

getting on shore were correspondingly diminished. They threw lifebuoys and made

every effort to save him but the current was so strong that he was swept out

and lost. There might have been a dozen on the fore part  (shown

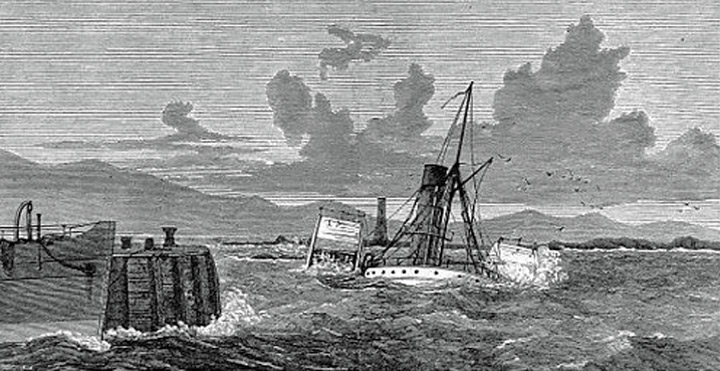

right in a print reproduced by kind permission of the copyright holders Illustrated

London News / Mary Evans Picture Library and available from www.prints-online.com)

when it came into the harbour. With the exception of that man, all the others

who were on that part of the vessel were saved. This occurred at the steamboat

pier which is the middle pier. The fore part of the vessel drifted into the

harbour and came right up till she stuck at the top. When the accident occurred,

the after part of the stern seemed to keep tight and men all ran to it. We heard

them screaming. About twenty minutes or half an hour after that, part of the

ship went down. Although it did so, however, it remained sufficiently above

the water to have saved anyone who had gone on the paddle boxes but there was

a great confusion and it did not seem to occur to the men to go there. They

remained on deck and a lot of them were washed away and drowned. Before the

vessel struck, I despatched one of the pilots to get together the lifeboat crew.

A scratch crew were got together and the boat was launched but the sea was so

strong that, pull as they may, they could not get out. The lifeboat was a first-class

one and was in good order. The harbour tug was despatched with what expedition

it could. This was before the lifeboat went out. It went as near the vessel

as it could and picked up two or three of the wreck. Finding that the lifeboat

could not get out, we signalled to the captain of the tug to come back if possible

to take it out but the storm was so great that he could not get his tug in position

to come back and some time was lost in that way. When he did return, however,

the lifeboat was towed out to the windward of the wreck and anchored. The lifeboat

was under the charge of Mr Breckenridge, pilot (for whose widow and children

a benefit football match was

played in 1880). The lifeboat went as near the wreck as it possibly could to

save those who were still remaining, five in number. Mr Bannatyne, captain of

the tug which went to the rescue of those on the after part of the vessel says:

We did all in our power to rescue the people but, in trying to reach the wreck,

our vessel always went to windward and we could not get at her. With considerable

difficulty, we did get pretty near. We took nine persons off, including the

Captain's wife. We threw out lines to them all and pulled them up in that way.

The Captain and his wife were lashed on the one line but it is not true that

the Captain's wife's sister was lashed on the same line. We were doing the best

we could to save them and we had brought his wife on board and had almost succeeded

in bringing himself in when he appeared to become very much exhausted and slipped

from the rope. The Captain did all he could to hold his wife out of the water

while we were bringing them across. Four men went out in a little boat at the

same time as we did but they did not succeed in rescuing anybody. They went

out in a little lull but the weather soon became stormy again and they could

do nothing. John Murdoch Johnstone, first mate, states: We left Glasgow on Saturday

10th bound to Shanghai with a channel pilot and two passengers on board. We

put into Waterford for the purpose of landing the pilot. We found that the ship

was unseaworthy and that she had broken some of her frame. The fore part of

the ship was all adrift. I think it was want of strength in the construction

of the vessel. She was condemned as unseaworthy in Waterford by the surveyors

and was coming back to Glasgow for repairs and to get strengthened. We left

Waterford with a fine night, moderate weather and wind from the north-west.

When the ship was abreast of the Maidens, the wind veered round to the south-west

and we held away on the other shore as the weather got thick. We steered for

the Cumbrae. The gale increased, the wind from the north-west till it blew a

hurricane. The ship would not answer her helm and was unmanageable. There were

four men at the wheel, a second officer named William Miller, two quartermasters

and a seaman. Three were washed overboard, the second officer and the two quartermasters.

The steamer was intended as a riverboat and could not stand a heavy sea. She

was 300 feet long and 33 feet beam. We made for Ardrossan to prevent the vessel

going in pieces and on entering the harbour, we struck against a rock. There

were four quartermasters, three of whom were drowned. Before the vessel struck,

one of the quartermasters got three of his fingers cut off by the wheel. He

was taken below to the cabin and was lying there when the accident occurred.

We had no time to get him out, however, and so the poor fellow was drowned.

The second mate was at the wheel when the vessel struck and immediately the

rudder touched the bottom and lifted him into the sea and no more was seen of

him. The vessel's decks were iron and they were all contracted before we came

to run into this place at all. She was measured for 3590 tons, builder's measurement

but was only half-fitted up, the intention being that when she got out to China

she could be fitted out completely in the same style as the river steamers in

America. When she left Glasgow, we had on board 840 tons of coals and water

and provisions which would bring up the weight to 950 tons. The ship is registered

in Glasgow as belonging to Messrs Russell and Company, Shangai, Messrs Baring

Brothers, bankers, London and Company being the agents in this country. Mr Moir,

pilot whom we took out with us from Glasgow came back with us from Waterford

and he had charge of the ship. She broke clean in two at the fore compartment

where we had discovered a defect on the passage to Waterford. The night was

as black and dirty as I have ever seen. I have been nineteen years at sea and

I never before saw such a bad night so far up the channel. This is the second

time I have been shipwrecked but the first time was nothing to this. Twenty-five

men came into the harbour on the fore part of the ship. The clothes of all the

men were in the fore part and have thus all been saved. None of the officers

saved any of their clothes. We struck about six o'clock. The ship was just a

perfect shell, not fit to contend with wind and water and sea. William Ortwin,

second engineer says: The ship parted immediately she struck. The fore part

drifted into the harbour but no white men were on that part. Those who remained

were left on the poop. There were three boats and we tried to get them out but

the men were washed away from them as fast as they got near them. They took

refuge on the quarterdeck. The pier was crowded with people but no assistance

came until about three-quarters of an hour after we struck. None of the ship's

boats were got out. They were all smashed by the heavy seas which blew across

the deck. The tug steamer was the first to come to our assistance. They made

four efforts to get close to us before she succeeded. Several of the crew jumped

into the water and ropes were immediately thrown out to them from the tug and

by these they were hauled on board. Others got hold of pieces of wood and tried

to save themselves by floating ashore on them. About six or eight got into the

tug at that time. The reason they the tug did not take us all off at once was

that the heavy sea which was running rendered the tug unmanageable. The Captain

and his wife were trying to get on board the tug and were being pulled by means

of a rope to the deck of the tug when the Captain became exhausted and had to

let go and was drowned. His wife was got on board. The tug took out the lifeboat

which let go her grappling irons and drifted astern of the steamer. It was with

great difficulty that those who remained were got into the lifeboat. A rope

was thrown to them and they were at last got on board. The order in which they

came was as follows: Miss Elliott, the Captain's sister-in-law; the Captain's

son, the first mate; Ortwin, Humphreys and the pilot. After much exertion, we

cleared the pier and got into the harbour. The crew of a vessel in the harbour

whose name I do not know, got out their own lifeboat and came out to the wreck

and did all they could to render assistance. H Lipscome, coastguardsman, Ardrossan

says: There are altogether five coastguardsmen here, the chief being George

Mays. Mays and two others are present on drill at Greenock and the fourth is

at Lamlash. Just now, I am the only man on duty here. Nine persons were rescued

by the steam tug, six by the lifeboat, six or seven by floating pieces of wreck

and several by the pilots throwing lines from the end of the pier. The rescued

persons are distributed among private houses in Ardrossan. The perilous position

of the vessel was not observed until about seven in the morning. It was not

quite daylight till that time. The lifeboat returned from the wreck at about

nine o'clock. There was a terrific sea running and it was with great difficulty

the people were brought in. Lines were thrown from the lifeboat to the sinking

vessel and the crew got hold of them and were dragged through the water. Thirty-six

are believed to have been saved leaving sixteen drowned. The three coastguardsmen

left for Greenock on Monday week and the man who went to Lamlash went on the

same day. I do not know when they are coming back but I telegraphed for them

today. Government sends us to drill any time it pleases. Additional and most

interesting particulars in connection with the melancholy loss of the Chusan

are supplied by the pilot in charge of the vessel, Mr R W Moir, Greenock, who

arrived at his home from Ardrossan in a very exhausted state on Wednesday evening.

The substance of his narrative is: I am a pilot in the Greenock district and

have acted in that capacity for about twelve months. Previous to that, I was

a shipmaster and I got my Master's Certificate in 1864. I left the Tail of the

Bank on Saturday 10th in charge of the Chusan and was to take her down-channel.

She was on her way out to China. We put into Waterford as it was found that

the vessel was not behaving satisfactorily. We had fine weather, a calm sea

and a slight breeze ahead but the vessel was making only about six knots an

hour and the bow was working up and down like a hinge. The engineers were also

wanting something to be done to the engines. Some of the officers and crew formed

a very bad opinion of the vessel and did not believe she was seaworthy. At the

request of the Captain, I remained on board till he would communicate with the

agents in London to see what would be done. Mr May, the surveyor to the company

that the Chusan belonged to came down from London to Waterford last Monday and

inspected the vessel along with the Captain and officers. It was found that,

besides the weakness in the bow, five of the frames on the starboard side and

two on the port side had given way. The judgement of the surveyors was that

she was not fit to go to China but she was fit enough to go back to Glasgow

where she would be thoroughly overhauled. The weather at this time was beautiful,

the wind from the west, the sea calm, the glass had been steadily rising and

the Captain resolved to start for the Clyde at once. We accordingly left Waterford

anchorage between nine and ten on Monday night. I studied to keep the vessel

in calm water and brought her all along the Irish coast. From Wicklow Head,

the wind began to increase and gradually it came on to blow a strong breeze.

I brought the vessel up into the smooth water past Belfast Lough and, with the

object of running before the sea, allowing that the wind would stop at west,

I headed for the Maidens. Off the Maidens, the wind changed to the south-west

and it was noticed with alarm that the glass was falling very rapidly and that

a storm was brewing. We then shaped the course for Pladda which we made for

three or four o'clock on Wednesday morning. The wind here slapped into the west

again and the storm had come down upon us with frightful violence. As we shaped

for the Clyde, we came across the north channel. There was something awful,

the seas running mountains high and the spray was blowing over the vessel, perfect

clouds. She was getting positively unmanageable and although four men were at

the wheel, the vessel could not answer her helm. After we got inside Pladda,

she would do nothing with us. The squalls were striking her broadside on and

she was at times entirely beyond our control. The morning was beside pitch dark.

The storm had waxed into a tempest, the vessel was drifting fast to leeward

and was only steaming eight or nine knots an hour and to add to our misfortune,

we had almost no idea where we were. This state of matters lasted for about

two hours and the only thing that I could find to tell me where we were was

the reflection in the sky from the ironworks in Ardrossan. The wind I know was

blowing us bodily to leeward but it would have been madness to try and force

the vessel into the storm. She was not fit for that and when we tried it, something

terrible would have happened. About dawn, when the weather had cleared up a

little, I made out Ardrossan lights on the lee bow. I knew then that it was

hopeless to try and weather Ardrossan for even though we had been able to 'wear'

the Chusan, she would afterwards have run right into land. We were being rapidly

being driven to the lee shore and I warned the Captain to prepare for the worst.

I was intimately acquainted with the entrance to Ardrossan harbour, knew thoroughly

both the position of the Horse Island

(shown

right in a print reproduced by kind permission of the copyright holders Illustrated

London News / Mary Evans Picture Library and available from www.prints-online.com)

when it came into the harbour. With the exception of that man, all the others

who were on that part of the vessel were saved. This occurred at the steamboat

pier which is the middle pier. The fore part of the vessel drifted into the

harbour and came right up till she stuck at the top. When the accident occurred,

the after part of the stern seemed to keep tight and men all ran to it. We heard

them screaming. About twenty minutes or half an hour after that, part of the

ship went down. Although it did so, however, it remained sufficiently above

the water to have saved anyone who had gone on the paddle boxes but there was

a great confusion and it did not seem to occur to the men to go there. They

remained on deck and a lot of them were washed away and drowned. Before the

vessel struck, I despatched one of the pilots to get together the lifeboat crew.

A scratch crew were got together and the boat was launched but the sea was so

strong that, pull as they may, they could not get out. The lifeboat was a first-class

one and was in good order. The harbour tug was despatched with what expedition

it could. This was before the lifeboat went out. It went as near the vessel

as it could and picked up two or three of the wreck. Finding that the lifeboat

could not get out, we signalled to the captain of the tug to come back if possible

to take it out but the storm was so great that he could not get his tug in position

to come back and some time was lost in that way. When he did return, however,

the lifeboat was towed out to the windward of the wreck and anchored. The lifeboat

was under the charge of Mr Breckenridge, pilot (for whose widow and children

a benefit football match was

played in 1880). The lifeboat went as near the wreck as it possibly could to

save those who were still remaining, five in number. Mr Bannatyne, captain of

the tug which went to the rescue of those on the after part of the vessel says:

We did all in our power to rescue the people but, in trying to reach the wreck,

our vessel always went to windward and we could not get at her. With considerable

difficulty, we did get pretty near. We took nine persons off, including the

Captain's wife. We threw out lines to them all and pulled them up in that way.

The Captain and his wife were lashed on the one line but it is not true that

the Captain's wife's sister was lashed on the same line. We were doing the best

we could to save them and we had brought his wife on board and had almost succeeded

in bringing himself in when he appeared to become very much exhausted and slipped

from the rope. The Captain did all he could to hold his wife out of the water

while we were bringing them across. Four men went out in a little boat at the

same time as we did but they did not succeed in rescuing anybody. They went

out in a little lull but the weather soon became stormy again and they could

do nothing. John Murdoch Johnstone, first mate, states: We left Glasgow on Saturday

10th bound to Shanghai with a channel pilot and two passengers on board. We

put into Waterford for the purpose of landing the pilot. We found that the ship

was unseaworthy and that she had broken some of her frame. The fore part of

the ship was all adrift. I think it was want of strength in the construction

of the vessel. She was condemned as unseaworthy in Waterford by the surveyors

and was coming back to Glasgow for repairs and to get strengthened. We left

Waterford with a fine night, moderate weather and wind from the north-west.

When the ship was abreast of the Maidens, the wind veered round to the south-west

and we held away on the other shore as the weather got thick. We steered for

the Cumbrae. The gale increased, the wind from the north-west till it blew a

hurricane. The ship would not answer her helm and was unmanageable. There were

four men at the wheel, a second officer named William Miller, two quartermasters

and a seaman. Three were washed overboard, the second officer and the two quartermasters.

The steamer was intended as a riverboat and could not stand a heavy sea. She

was 300 feet long and 33 feet beam. We made for Ardrossan to prevent the vessel

going in pieces and on entering the harbour, we struck against a rock. There

were four quartermasters, three of whom were drowned. Before the vessel struck,

one of the quartermasters got three of his fingers cut off by the wheel. He

was taken below to the cabin and was lying there when the accident occurred.

We had no time to get him out, however, and so the poor fellow was drowned.

The second mate was at the wheel when the vessel struck and immediately the

rudder touched the bottom and lifted him into the sea and no more was seen of

him. The vessel's decks were iron and they were all contracted before we came

to run into this place at all. She was measured for 3590 tons, builder's measurement

but was only half-fitted up, the intention being that when she got out to China

she could be fitted out completely in the same style as the river steamers in

America. When she left Glasgow, we had on board 840 tons of coals and water

and provisions which would bring up the weight to 950 tons. The ship is registered

in Glasgow as belonging to Messrs Russell and Company, Shangai, Messrs Baring

Brothers, bankers, London and Company being the agents in this country. Mr Moir,

pilot whom we took out with us from Glasgow came back with us from Waterford

and he had charge of the ship. She broke clean in two at the fore compartment

where we had discovered a defect on the passage to Waterford. The night was

as black and dirty as I have ever seen. I have been nineteen years at sea and

I never before saw such a bad night so far up the channel. This is the second

time I have been shipwrecked but the first time was nothing to this. Twenty-five

men came into the harbour on the fore part of the ship. The clothes of all the

men were in the fore part and have thus all been saved. None of the officers

saved any of their clothes. We struck about six o'clock. The ship was just a

perfect shell, not fit to contend with wind and water and sea. William Ortwin,

second engineer says: The ship parted immediately she struck. The fore part

drifted into the harbour but no white men were on that part. Those who remained

were left on the poop. There were three boats and we tried to get them out but

the men were washed away from them as fast as they got near them. They took

refuge on the quarterdeck. The pier was crowded with people but no assistance

came until about three-quarters of an hour after we struck. None of the ship's

boats were got out. They were all smashed by the heavy seas which blew across

the deck. The tug steamer was the first to come to our assistance. They made

four efforts to get close to us before she succeeded. Several of the crew jumped

into the water and ropes were immediately thrown out to them from the tug and

by these they were hauled on board. Others got hold of pieces of wood and tried

to save themselves by floating ashore on them. About six or eight got into the

tug at that time. The reason they the tug did not take us all off at once was

that the heavy sea which was running rendered the tug unmanageable. The Captain

and his wife were trying to get on board the tug and were being pulled by means

of a rope to the deck of the tug when the Captain became exhausted and had to

let go and was drowned. His wife was got on board. The tug took out the lifeboat

which let go her grappling irons and drifted astern of the steamer. It was with

great difficulty that those who remained were got into the lifeboat. A rope

was thrown to them and they were at last got on board. The order in which they

came was as follows: Miss Elliott, the Captain's sister-in-law; the Captain's

son, the first mate; Ortwin, Humphreys and the pilot. After much exertion, we

cleared the pier and got into the harbour. The crew of a vessel in the harbour

whose name I do not know, got out their own lifeboat and came out to the wreck

and did all they could to render assistance. H Lipscome, coastguardsman, Ardrossan

says: There are altogether five coastguardsmen here, the chief being George

Mays. Mays and two others are present on drill at Greenock and the fourth is

at Lamlash. Just now, I am the only man on duty here. Nine persons were rescued

by the steam tug, six by the lifeboat, six or seven by floating pieces of wreck

and several by the pilots throwing lines from the end of the pier. The rescued

persons are distributed among private houses in Ardrossan. The perilous position

of the vessel was not observed until about seven in the morning. It was not

quite daylight till that time. The lifeboat returned from the wreck at about

nine o'clock. There was a terrific sea running and it was with great difficulty

the people were brought in. Lines were thrown from the lifeboat to the sinking

vessel and the crew got hold of them and were dragged through the water. Thirty-six

are believed to have been saved leaving sixteen drowned. The three coastguardsmen

left for Greenock on Monday week and the man who went to Lamlash went on the

same day. I do not know when they are coming back but I telegraphed for them

today. Government sends us to drill any time it pleases. Additional and most

interesting particulars in connection with the melancholy loss of the Chusan

are supplied by the pilot in charge of the vessel, Mr R W Moir, Greenock, who

arrived at his home from Ardrossan in a very exhausted state on Wednesday evening.

The substance of his narrative is: I am a pilot in the Greenock district and

have acted in that capacity for about twelve months. Previous to that, I was

a shipmaster and I got my Master's Certificate in 1864. I left the Tail of the

Bank on Saturday 10th in charge of the Chusan and was to take her down-channel.

She was on her way out to China. We put into Waterford as it was found that

the vessel was not behaving satisfactorily. We had fine weather, a calm sea

and a slight breeze ahead but the vessel was making only about six knots an

hour and the bow was working up and down like a hinge. The engineers were also

wanting something to be done to the engines. Some of the officers and crew formed

a very bad opinion of the vessel and did not believe she was seaworthy. At the

request of the Captain, I remained on board till he would communicate with the

agents in London to see what would be done. Mr May, the surveyor to the company

that the Chusan belonged to came down from London to Waterford last Monday and

inspected the vessel along with the Captain and officers. It was found that,

besides the weakness in the bow, five of the frames on the starboard side and

two on the port side had given way. The judgement of the surveyors was that

she was not fit to go to China but she was fit enough to go back to Glasgow

where she would be thoroughly overhauled. The weather at this time was beautiful,

the wind from the west, the sea calm, the glass had been steadily rising and

the Captain resolved to start for the Clyde at once. We accordingly left Waterford

anchorage between nine and ten on Monday night. I studied to keep the vessel

in calm water and brought her all along the Irish coast. From Wicklow Head,

the wind began to increase and gradually it came on to blow a strong breeze.

I brought the vessel up into the smooth water past Belfast Lough and, with the

object of running before the sea, allowing that the wind would stop at west,

I headed for the Maidens. Off the Maidens, the wind changed to the south-west

and it was noticed with alarm that the glass was falling very rapidly and that

a storm was brewing. We then shaped the course for Pladda which we made for

three or four o'clock on Wednesday morning. The wind here slapped into the west

again and the storm had come down upon us with frightful violence. As we shaped

for the Clyde, we came across the north channel. There was something awful,

the seas running mountains high and the spray was blowing over the vessel, perfect

clouds. She was getting positively unmanageable and although four men were at

the wheel, the vessel could not answer her helm. After we got inside Pladda,

she would do nothing with us. The squalls were striking her broadside on and

she was at times entirely beyond our control. The morning was beside pitch dark.

The storm had waxed into a tempest, the vessel was drifting fast to leeward

and was only steaming eight or nine knots an hour and to add to our misfortune,

we had almost no idea where we were. This state of matters lasted for about

two hours and the only thing that I could find to tell me where we were was

the reflection in the sky from the ironworks in Ardrossan. The wind I know was

blowing us bodily to leeward but it would have been madness to try and force

the vessel into the storm. She was not fit for that and when we tried it, something

terrible would have happened. About dawn, when the weather had cleared up a

little, I made out Ardrossan lights on the lee bow. I knew then that it was

hopeless to try and weather Ardrossan for even though we had been able to 'wear'

the Chusan, she would afterwards have run right into land. We were being rapidly

being driven to the lee shore and I warned the Captain to prepare for the worst.

I was intimately acquainted with the entrance to Ardrossan harbour, knew thoroughly

both the position of the Horse Island  (shown

right in 2011) and the Crinan Rock and as I made out the light on the pier-head,

I told the Captain that our last chance would be to try to enter the harbour.

He said not to mind much what might happen to the ship but to do my utmost to

save the lives on board. The engineers and stokers were below getting up the

steam as much as possible but I was told it was never higher than thirty pounds.

We were making for Ardrossan from the south-westward and the wind was carrying

us to leeward, broadside on but we used the most strenuous efforts to get the

vessel's head right into the harbour. The entrance is a very dangerous one at

any time even with a vessel that steers well but with the Chusan, the risk was

dreadful. The squalls were coming down on her from all directions, catching

her big paddle boxes and and the great covering of her boilers like big sails

and I saw that the only possibility of getting her in was by working her engines

ahead and astern and to allow her to drift broadside in. I verily believe we

would have managed that but by some unfortunate or overlook, the engines would

not work reversely by steam and the working of the valves had to be done by

manual labour. When the vessel was manoeuvring in this way, she was struck by

a sea and borne onwards but instead of the stern remaining fast on the rock

and the stern slewing in as we had calculated, the vessel parted and the after

portion sunk and the fore compartment floated into the harbour. Even then, had

the people on shore been able to work the rocket apparatus, not a person on

board need have been lost as we were quite close to the pier. I had kept my

post all the time and was left in the after portion of the vessel along with

the Captain's son, Miss Elliott, the second engineer, the mate and the purser.

I was the last man that was got off the deck alive. I was in a very exhausted

condition for I had been clinging to the masthead for nearly two hours and by

that time had scarcely any clothes on. I had besides nearly two or three times

been swept away. I cannot too warmly express my thanks for the kind way that

the people of Ardrossan treated me. I was taken to the house of Mr Robertson,

assistant harbourmaster, and after recovering somewhat, I was supplied by him

with clothes which enabled me to set out for Greenock. My conscience is clear

that I did the very utmost that lay in my power to save the vessel and those

on board. From six o'clock on Monday morning to the wreck on Wednesday morning,

I had never had any rest except two hours that I lay down below before the storm

had come on and all the time the storm lasted I was never off the bridge except

occasionally when I assisted the men at the wheel. The crew consisted of George

C Johnson, master, belonging to Salem, United States of America; John Murdoch

Johnstone, first mate, belonging to Glasgow; William Miller, second mate, belonging

to Fort William; William Gardner, chief engineer, belonging to Leith, a married

man with a family; William Ortwin, second engineer, belonging to Liverpool where

he was married only four weeks ago; William G Wrench, third engineer, belonging

to Abernethy; George Marr, fourth engineer, a native of Aberdeen but residing

in Glasgow and Edwin Humphreys, purser, belonging to Salem. These were whites

and there were also the following coloured men: three stewards, two cooks, fifteen

firemen and eighteen sailors. Besides these, there were on board Mrs Johnson,

the Captain's wife; his son George, about four years of age; his wife's sister,

Miss E Elliott; Captain King, a passenger and Mr Moir, the pilot in charge of

the vessel. Of those drowned, with the exception only of two, the Captain and

the second mate, were coloured men. The latter part of the ship still lies aground

close to the rock. The boilers and machinery are lying about eight or ten feet

under water and are apparently quite sound. The paddle boxes rise above water

and about eight or nine feet of the funnel is also observable. On Wednesday

night, several of the crew slept in their usual berth as comfortably as nothing

has On Wednesday night, several of the crew slept in their usual berths in the

forecastle as comfortably as nothing has happened to the vessel. The Chusan

was fully insured. Grappling operation were carried out on Thursday and several

articles were recovered from the wreck. Lord Eglinton visited the scene of the

wreck today, Friday. The chronometer of the ill-fated vessel was taken ashore

on Thursday afternoon and was found to have stopped at five minutes to seven

o'clock. Eighty-one pounds of tobacco was also brought ashore and was seized

by the coastguard. Two bracelets were picked up and one of them was said by

the Captain's sister-in-law to be from a box containing twelve rings and twelve

bracelets belonging to Captain Johnson. The box has not been recovered. Today

Friday, the men were mustered at the Custom House (shown

below in 2007 prior to its demolition in 2010) for the purpose of being discharged.

It appears they got a month's pay in advance and the proposed settlement is

that the men accept of a free pass to Glasgow furnished by Mr Arthur Guthrie,

the honorary secretary of the Royal National Lifeboat Institute here and accept

a gratuity of five shillings each given in the name of Captain King. The mate,

Mr Johnstone, who exerted himself so heroically and has lost everything, they

propose to treat in the same way. The suit of the clothes he is going about

in have been lent him by some benevolent person. The men have refused to accept

these terms and declare their intention to stick by the part of the vessel which

floated into the harbour. The ship's articles were signed by the men

for six months. Most of the men have their effects safe in the fore part of

the ship but Mr Johnstone's case is one of particular hardship. Two lads of

colour who had swam ashore were taken on board a brig in the harbour and, as

they were greatly exhausted, they were kindly entertained by the master till

Thursday morning when they were able to step ashore and present themselves to

their comrades. Most cordial were the greetings they received from those warm-hearted

fellows, one of them remarking he had passed a very sad night on account of

these boys as he thought they had been lost. Another man on Tuesday morning

unexpectedly made his appearance on board fore part of the Chusan where a number

of crew had passed the night. They asked him where he had been when it turned

out he had been taken in by some kind person and lodged for the night.

(shown

right in 2011) and the Crinan Rock and as I made out the light on the pier-head,

I told the Captain that our last chance would be to try to enter the harbour.

He said not to mind much what might happen to the ship but to do my utmost to

save the lives on board. The engineers and stokers were below getting up the

steam as much as possible but I was told it was never higher than thirty pounds.

We were making for Ardrossan from the south-westward and the wind was carrying

us to leeward, broadside on but we used the most strenuous efforts to get the

vessel's head right into the harbour. The entrance is a very dangerous one at

any time even with a vessel that steers well but with the Chusan, the risk was

dreadful. The squalls were coming down on her from all directions, catching

her big paddle boxes and and the great covering of her boilers like big sails

and I saw that the only possibility of getting her in was by working her engines

ahead and astern and to allow her to drift broadside in. I verily believe we

would have managed that but by some unfortunate or overlook, the engines would

not work reversely by steam and the working of the valves had to be done by

manual labour. When the vessel was manoeuvring in this way, she was struck by

a sea and borne onwards but instead of the stern remaining fast on the rock

and the stern slewing in as we had calculated, the vessel parted and the after

portion sunk and the fore compartment floated into the harbour. Even then, had

the people on shore been able to work the rocket apparatus, not a person on

board need have been lost as we were quite close to the pier. I had kept my

post all the time and was left in the after portion of the vessel along with

the Captain's son, Miss Elliott, the second engineer, the mate and the purser.

I was the last man that was got off the deck alive. I was in a very exhausted

condition for I had been clinging to the masthead for nearly two hours and by

that time had scarcely any clothes on. I had besides nearly two or three times

been swept away. I cannot too warmly express my thanks for the kind way that

the people of Ardrossan treated me. I was taken to the house of Mr Robertson,

assistant harbourmaster, and after recovering somewhat, I was supplied by him

with clothes which enabled me to set out for Greenock. My conscience is clear

that I did the very utmost that lay in my power to save the vessel and those

on board. From six o'clock on Monday morning to the wreck on Wednesday morning,

I had never had any rest except two hours that I lay down below before the storm

had come on and all the time the storm lasted I was never off the bridge except

occasionally when I assisted the men at the wheel. The crew consisted of George

C Johnson, master, belonging to Salem, United States of America; John Murdoch

Johnstone, first mate, belonging to Glasgow; William Miller, second mate, belonging

to Fort William; William Gardner, chief engineer, belonging to Leith, a married

man with a family; William Ortwin, second engineer, belonging to Liverpool where

he was married only four weeks ago; William G Wrench, third engineer, belonging

to Abernethy; George Marr, fourth engineer, a native of Aberdeen but residing

in Glasgow and Edwin Humphreys, purser, belonging to Salem. These were whites

and there were also the following coloured men: three stewards, two cooks, fifteen

firemen and eighteen sailors. Besides these, there were on board Mrs Johnson,

the Captain's wife; his son George, about four years of age; his wife's sister,

Miss E Elliott; Captain King, a passenger and Mr Moir, the pilot in charge of

the vessel. Of those drowned, with the exception only of two, the Captain and

the second mate, were coloured men. The latter part of the ship still lies aground

close to the rock. The boilers and machinery are lying about eight or ten feet

under water and are apparently quite sound. The paddle boxes rise above water

and about eight or nine feet of the funnel is also observable. On Wednesday

night, several of the crew slept in their usual berth as comfortably as nothing

has On Wednesday night, several of the crew slept in their usual berths in the

forecastle as comfortably as nothing has happened to the vessel. The Chusan

was fully insured. Grappling operation were carried out on Thursday and several

articles were recovered from the wreck. Lord Eglinton visited the scene of the

wreck today, Friday. The chronometer of the ill-fated vessel was taken ashore

on Thursday afternoon and was found to have stopped at five minutes to seven

o'clock. Eighty-one pounds of tobacco was also brought ashore and was seized

by the coastguard. Two bracelets were picked up and one of them was said by

the Captain's sister-in-law to be from a box containing twelve rings and twelve

bracelets belonging to Captain Johnson. The box has not been recovered. Today

Friday, the men were mustered at the Custom House (shown

below in 2007 prior to its demolition in 2010) for the purpose of being discharged.

It appears they got a month's pay in advance and the proposed settlement is

that the men accept of a free pass to Glasgow furnished by Mr Arthur Guthrie,

the honorary secretary of the Royal National Lifeboat Institute here and accept

a gratuity of five shillings each given in the name of Captain King. The mate,

Mr Johnstone, who exerted himself so heroically and has lost everything, they

propose to treat in the same way. The suit of the clothes he is going about

in have been lent him by some benevolent person. The men have refused to accept

these terms and declare their intention to stick by the part of the vessel which

floated into the harbour. The ship's articles were signed by the men

for six months. Most of the men have their effects safe in the fore part of

the ship but Mr Johnstone's case is one of particular hardship. Two lads of

colour who had swam ashore were taken on board a brig in the harbour and, as

they were greatly exhausted, they were kindly entertained by the master till

Thursday morning when they were able to step ashore and present themselves to

their comrades. Most cordial were the greetings they received from those warm-hearted

fellows, one of them remarking he had passed a very sad night on account of

these boys as he thought they had been lost. Another man on Tuesday morning

unexpectedly made his appearance on board fore part of the Chusan where a number

of crew had passed the night. They asked him where he had been when it turned

out he had been taken in by some kind person and lodged for the night.

Ardrossan and Saltcoats Herald, 24 October 1874

CAPTAIN JOHNSON'S BODY SHIPPED HOME